Photo: Colin Waters / Alamy stock Photo

WWI - Trench warfare - Canadian troops stand ready to repel a German attack. One is using a periscope to safely see over the trench top.

Nicolas Provencher is a former infantryman in the Army Reserve. During his 6 years with the Voltigeurs de Québec, he completed a bachelor’s degree in History and a Diplôme d’études supérieures spécialisées en enseignement collégial (Diploma of specialized graduate studies in college teaching) from Université Laval. In 2016, he switched to the regular force as a Training Development Officer (TDO). He was transferred to 2 Wing Bagotville in 2017 and, in 2019, took up a TDO position with CANSOFCOM. In 2020, he completed a master’s degree in War Studies at the Royal Military College in Kingston. He is currently posted at the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn, Estonia, as TDO and Canadian representative.

On the night of November 16-17, 1915, at the Petite Douve near Saint-Éloi in France, a group of soldiers from the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade were preparing to carry out the very first Canadian raid.Footnote1

At 2 a.m. on November 17, the attack was launched. Three teams of grenadiers took over the trenches, while a team of signallers took charge of the prisoners and established communications with headquarters. Meanwhile, another team set up a fire base to cover the attackers’ retreat. The attack was a success. The Canadians withdrew and the prisoners were brought behind the lines without too much trouble. Such operations, which were in fact brief incursions into enemy trenches, were part of the everyday life of the men in the trenches.Footnote2 Patrols were much more frequent and smaller scale than trench raids. They were usually led by small groups of scouts. Unlike raids, which focused on enemy trenches, patrols had “No Man’s Land” as their playground. The primary aim was to gather information about the enemy and the terrain.

This study assesses the influence of trench raids and patrols on the conduct of war. We therefore seek to measure the importance of raids and patrols in the overall gathering of military intelligence. So why send out a patrol or order the men leading a raid to gather information when commanders had other options, such as aerial reconnaissance?

We will use the example of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division in the Ypres sector in the summer of 1916 to demonstrate that trench raids and patrols were essential for gathering intelligence and thus building and maintaining situational awareness. In a military context, good situational awareness is characterized by a precise and accurate perception of one’s environment and of the elements key to the success of a mission, with the ability to quickly analyze them and then attempt to establish projections of the enemy’s intentions. Level 1 is the gathering of local information. Key elements include the location of enemy (and friendly) troops, their strength, armament, and morale, as well as terrain characteristics. Level 2 involves both combining this information and interpreting it to understand the consequences of the enemy’s actions. In short, all level 1 information is assembled like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle to form an overall picture of the environment. Following systematic analysis (level 2), this information becomes useful intelligence in the decision-making process. Level 3 involves using this intelligence to anticipate enemy action and make informed decisions about our own actions. Completion of level 3 represents the final stage in the process of acquiring situational awareness.

THE ORIGIN OF TRENCH RAIDS

An examination of the war diaries of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division reveals the importance of trench raids and patrols in the soldiers’ daily lives, with the terms enterprises, minor operations, patrols or raids recurring dailyFootnote3. By their very nature, raids and patrols required the best soldiers, those with specific qualities such as courage and aggressiveness. But these operations were potentially very costly in terms of men and equipment. So why did they seem to be used so regularly? Two key concepts will help explain this: the “cult of the offensive” and the “live and let live system.”

The Cult of the Offensive and the Live and Let Live System

The cult of the offensive dominated Western military and strategic thinking in the 19th and 20th centuries.Footnote4 In Germany, military theorists such as Alfred von Schlieffen, Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Molkte, and Friedrich von Bernhardi argued that offensive action was far more effective than defensive action.Footnote5 French doctrine, based on the “offensive à outrance” approach, was along the same lines.Footnote6 General Joseph Joffre insisted that no law other than that of the offensive should be tolerated. This perspective was in fact the result of a combination of three factors: concern about increasing firepower, distrust of working-class recruits, and faith in a structured, orderly, and above all decisive battlefield.Footnote7 Logically, in a war between two European armies, victory would go to the first to attack.

During World War I, keeping troops on the alert between major offensives was a constant concern for staffs on both sides. When the Western front was at a standstill, a certain inertia set in, what Tony Ashworth calls “the live-and-let-live system.”Footnote8 It was in fact an unofficial and illicit truce in which both sides ceased fighting by mutual agreement. The aim was to reduce the risk of death and injury, and thus improve the relative comfort of the men living in the trenches. These truces may have lasted a few minutes, just long enough for lunch. The most common example is the unofficial truce of Christmas 1914, when opposing camps in various sectors gathered in “No Man’s Land” to discuss and “celebrate.”Footnote9

However, “live and let live” was a far more complex system than one might expect. According to Ashworth, it could manifest itself in three different ways: fraternization, inertia, and ritualization. The Christmas truce of 1914 is a good example of fraternization. This type of truce lasted from a few minutes to several months, depending on the sector. Inertia set in when both parties communicated indirectly with each other to avoid provocation or other aggressive action.Footnote10 Ritualization was sometimes in the form of a pseudo-operation, as in the case of soft raids; instead of patrolling No Man’s Land, some men would take refuge in a crater, only to return a few hours later.Footnote11

To curb this live-and-let-live phenomenon, the obligation to conduct trench raids was ordered in February 1915 by Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force.Footnote12 His successor, General Sir Douglas Haig, who had also become aware of the inertia at the front, continued this policy, but on a larger scale. By 1916, the hope of a decisive battle had been dashed, and the war of attrition began. Trench raids were part of this new overall strategy. Many, including Haig, were convinced that the war would be won by maintaining continuous pressure on the enemy. But to achieve this, it was essential to put an end to the major strategic problem of “live and let live” by implementing a policy of systematic raids.Footnote13 Orders were issued, and pressure increased right down the chain of command. Depending on the sector, men from every Canadian battalion patrolled No Man’s Land virtually every night.Footnote14

Tactically, patrolling No Man’s Land offered several advantages. It is essential to understand that trench raids were part of an overall evolution in warfare, beginning with the application of British doctrine to which the Canadian Expeditionary Force was subject as part of an imperial force. This doctrine, which was ill-suited to the conflicts of the 20th century, was hardly ever called into question, but everything changed after the Battle of the Somme in 1916. After German machine guns and artillery had decimated whole waves of men, British military leaders were forced to admit that doctrinal changes were needed. Learning from the French and even the Germans, the use of supporting weapons and offensive tactics changed considerably, putting the emphasis on firing and movement. In anticipation of major offensives, men needed to familiarize themselves with these innovations to develop sufficient confidence in themselves and their equipment.Footnote15 In the meantime, raids were able to fulfill this role, allowing them to test new weapons and tactics on a smaller scale.Footnote16 As Tim Cook points out: “By raiding and patrolling, the Canadian experimented with new battle theories and tactics, while gaining experience in the planning and carrying out of operations. With so few large-scale engagements taking place, it was the trench patrol and raid that became the laboratory of battle.”Footnote17

Also, as will be discussed in the next chapter, raids and patrols enabled soldiers to gather information on No Man’s Land. Of course, the Allies and Germans were in constant battle. The geography of the terrain changed considerably from battle to battle, and even from day to day, due to the nature of the fighting. Patrolled by night and shelled by day, this stretch of land posed an extreme threat to the soldiers. Even when it seemed unoccupied, it was teeming with activity of all kinds. The various defensive structures were destroyed and rebuilt daily.Footnote18 It’s not surprising, then, that commanding officers ordered patrols on an almost daily basis. This search for information remained at the heart of commanders’ concerns. Raids and patrols were therefore the tactics of choice for maintaining situational awareness.

It’s important to mention that raids and patrols were just one way of gathering information about the enemy and the terrain. Aerial reconnaissance also played an important role as a means of gathering intelligence during World War I. It should be noted that Canada didn’t have its own air force at the time, so the 20,000 or so Canadian airmen and mechanics served either in the Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Naval Air Service, or the Royal Air Force.

The limits of aerial reconnaissance

As early as 1914, aerial reconnaissance was also an important means of gathering intelligence. However, reconnaissance missions became increasingly dangerous for the airmen, especially with the advent of Fokker aircraft, which could fire through their propellers. Between November 1915 and January 1916, German pilots shot down an average of four British aircraft for every one they lost.Footnote19 Flying over the battlefields, sometimes at very low altitudes, the pilot and his observer became prime targets for machine guns. In this context, sending planes over No Man’s Land instead of ground troops was not necessarily an economical use of resources. It is also important to mention the technical limitations of aerial observation. It was not until February 1915 that aircraft were equipped with cameras capable of taking moving pictures.Footnote20 The technological evolution of cameras was so slow that even in 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, photographs could not be used as much as commanders wanted. Therefore, patrols were usually sent out to confirm observers’ claims so that no doubts remained.Footnote21 Also, the quality of the photographs simply prevented certain vital information from being distinguished, such as the depth of craters, the type of vegetation, the state of the barbed wire, and so on.Footnote22

In short, commanders could not rely entirely on aerial intelligence to build their situational awareness. The information provided by the airmen was certainly important and useful to the conduct of the war, but far too many variables such as technology and weather influenced the results. Much of the information needed to develop and maintain tactical situational awareness unfortunately eluded the airmen, leaving them with no choice but to send in reconnaissance. In fact, patrols and raids were essential complements to aerial observation. The men on the ground could not only confirm information gathered from the air, but also detect important details that the cameras of the time were unable to capture. In this technological and industrial warfare, human judgment remained essential for the analysis of certain information. The situation on the Saint-Éloi front in 1916, discussed in the next chapter, is a case in point.

SPRING 1916: THE 2ND CANADIAN INFANTRY DIVISION ON THE FRONT

In January 1916, the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions occupied the southern Ypres salient. Until April, the 2nd Division did not take part in any major battles. Its task was limited to harassing the Germans.Footnote23 The situation changed, however, when the division was sent to the Saint-Éloi sector.

The 2nd Canadian Division at Saint-Éloi

Between February 8 and 19, 1916, in anticipation of the Battle of Verdun, the Germans launched a diversionary offensive in the 5th British Corps sector. On February 14, they seized a wooded mound on the north bank of the Ypres-Comines canal. In response, General Plumer, commander of the British 2nd Army, to which the Canadian Expeditionary Force and the 5th Corps reported, ordered an attack on the Saint-Éloi salient, just over a kilometre to the southwest.Footnote24 The Germans were well entrenched there and could effectively shell the British positions.Footnote25 Unbeknownst to the Germans, British engineers had dug galleries and laid mines under the German trenches. The explosion took place at 4:15 a.m. on March 27, 1916, leaving seven large craters and several smaller ones. The assault was launched immediately afterwards.Footnote26

In less than half an hour, the British captured three craters, but it took a week to capture the last one. On April 3, the 3rd Division finally occupied the Saint-Éloi front, but it became increasingly clear that without reinforcements, they could neither advance nor hold their position.Footnote27

In fact, the Canadian Expeditionary Force was scheduled to take over on the night of April 6-7. However, as a German counter-attack was anticipated, the operation was brought forward to the night of April 3-4.Footnote28 They were relieved under enemy artillery fire. British dead and wounded littered the ground, their exhausted brothers-in-arms trying their best to bring them back to the rear. The operation continued until the morning of April 5. On April 6, the dreaded counter-attack began. In just a few hours, the Germans regained possession of the territory lost between March 27 and April 3. In turn, the Canadians, now occupying the position, launched an attack to retake the craters. There was total confusion. Inexperienced soldiers had trouble navigating and finding their bearings. General Richard Turner and his staff had no idea what was happening at the front.Footnote29 In fact, a string of inaccurate, even false, reports were sent to headquarters. On April 16, following aerial reconnaissance, General Alderson realized the scale of the catastrophe. He noticed that the Germans controlled most of the strongholds. The planned counter-attacks were cancelled and the fighting gradually ceased.Footnote30

The quest for situational awareness

In preparation for relief on site, the transfer of information was crucial. Although the 3rd British Division’s Relief Order No. 70 clearly stated that all relevant information, including topographic maps, photographs, and defence diagrams, was to be shared with the 2nd Division, there is no evidence that this passage of information was carried out effectively.Footnote31 In fact, according to intelligence reports from the 2nd Canadian Division, situational awareness was very poor. General Turner, commander of the 2nd Canadian Division, attests to this in his account of events. “The men of the 3rd Division were very much exhausted. […] They had evidently suffered from shelling during the day, and they were too fatigued to be able to give much information to the relieving troops.”Footnote32 When Turner assumed command in Saint-Éloi, the information received by the chain of command about his new sector was sketchy.Footnote33 All he could count on was some advice from the British 3rd Division commander, but nothing could improve his situational awareness.Footnote34

As soon as the relief was completed, the men of the 2nd Division were kept very busy. Until April 9, the priority was to consolidate the new line.Footnote35 It was a colossal task. So much so that on April 8, two companies of the 2nd Pioneer Battalion were attached to the infantry battalions for three days and three nights.Footnote36 On the night of April 6-7, a number of patrols were sent into No Man’s Land. They returned with prisoners, but little useful information for the commanders. Level 1 situational awareness of the 2nd Division, newly arrived in the area, was almost non-existent. In fact, the first few days’ reports offered little useful information for building situational awareness. The information gathered and shared was very vague, imprecise or, worse still, false.Footnote37 No observation posts could be set up, and the scouts were unable to reconnoitre No Man’s Land due to German bombing raids.Footnote38 Thus, during the day and night of April 8, a few patrols were sent into enemy trenches, but the results were the same. Lieutenant Nichols, a member of the 21st Battalion and commander of the patrol, reported: “The opinion of the patrol is that trench from 73 to 96 is well manned and that enemy are working hard on it.”Footnote39 This information was based solely on the sounds the soldiers could hear, as they were unable to get close enough to gather more precise information.

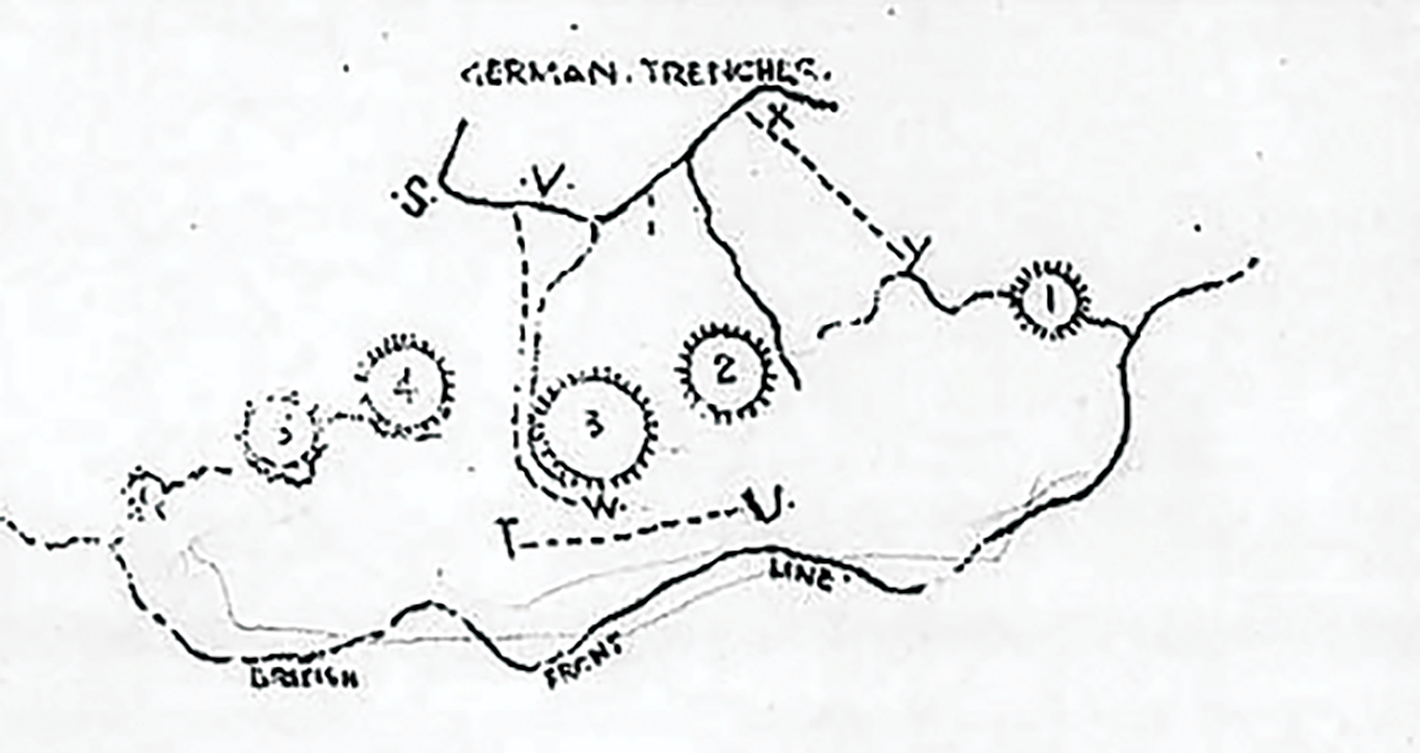

A look at other reports shows that the paucity of information gathered (level 1) had a considerable impact on the quality of the information disseminated, and consequently on level 2 situational awareness. Very few resources such as topographic maps were available. As shown in the document in Figure 1, those that were shared were rudimentary and contained little useful planning information. At the beginning of April 1916, Canadian situational awareness was limited and did not allow senior officers to anticipate German actions or even plan their own. In fact, the commanders had no overall view of the battlefield. The impact was disastrous, and the battle that followed and ended on April 16 was to make matters considerably worse.

Source: BAC, WD, “2nd Canadian Division – General Staff (1916/03/01–1916/04/30).” Available at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca.

Click to enlarge imageFigure 1: Sketch submitted following a patrol (April 13, 1916)

General Plumer decided to take the risk of moving ahead of the changeover between his British and Canadian troops, despite the inexperience of the latter. As a result, after the changeover, the Canadians had to work extremely hard to consolidate their position and gather relevant information. Nevertheless, in those few weeks, important lessons were learned and the situation quickly improved.

RAIDS AND PATROLS TO RESTORE SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

On April 16, when the battle of Saint-Éloi was over, the men of the 2nd Division unfortunately couldn’t catch their breath. They were disorganized and scattered. The officers had only fragmentary situational awareness. Consequently, considerable effort was put into consolidating positions. Once firmly established, the staff could finally plan offensive operations to harass the enemy and gather information on its positions. This process of consolidation and acquisition of situational awareness took place mainly in May and July 1916. During these few short weeks, Canadian soldiers were extremely active in the Saint-Éloi sector.

At tactical and operational levels, officers were primarily interested in German defences, including trenches, barbed wire networks, observation posts, machine-gun posts, and artillery positions.Footnote40 A section called Work Party in the weekly intelligence reports is of interest in this respect. It records all enemy activity relating to work done at the position, including the type of construction undertaken and, if possible, the approximate number of men working on it. This enabled the Canadian command to know the location of new German strongholds, track their progress, and adjust to the new positions.Footnote41 This information was usually first reported by aerial reconnaissance, and men were then dispatched to confirm the reports received. In fact, due to their distance from the target, the airmen were unable to identify certain elements with precision. Often, important additional information was brought back by the infantry. For example, on the night of July 26-27, men from the 18th Battalion (4th Brigade) raided enemy positions at Piccadilly Farm and noted that the barbed wire network they had previously observed was much denser than expected. This information was extremely important in planning future operations. It could influence a number of variables, such as the duration of the operation and the allocation of personnel and equipment.Footnote42

Acquiring information was a tedious task, as enemy installations evolved while new ones appeared daily.Footnote43 In fact, aerial and, above all, ground reconnaissance had to be carried out every day to provide commanders with the most up-to-date information possible. The identification of enemy obstacles and their progression enabled intelligence officers to annotate topographic maps to create level 2 situational awareness. The contribution of raids and patrols was considerable in this sense, because the command obtained information that was difficult to observe from the air.

Raids and patrols in Saint-Éloi in the summer of 1916

The priority for the Canadians in May 1916 was to consolidate their position. Several work crews were sent ahead. The 5th Brigade alone did a considerable amount of work. On May 8, the 22nd and 26th Battalions dispatched 800 soldiers to No Man’s Land. The next day, 650 men from the 24th and 26th Battalions were sent, and on May 10, the 24th and 22nd Battalions detached 325 men to carry out the same mission. Finally, on May 25, 775 soldiers from the 22nd, 25th, and 26th Battalions went to work. Their main task was to build barbed wire and drainage networks. The objective was to build as many defensive structures as possible, so that engineers could then make adjustments where necessary.Footnote44

By mid-June, the line was actually in better condition, enabling more effort to be put into gathering information and building situational awareness. From the night of June 30, the 22nd Battalion, occupying the right, and the 26th, covering the left, each prepared a raid on the enemy trenches. Their main objective was to identify the enemy unit by capturing prisoners or equipment.Footnote45 For the 26th, the operation was a success. A ton of information was brought back to headquarters, including the following:

The trench was 6 foot deep and in excellent condition with bath mats and board fire steps. No dugouts were observed. A careful search was made for gas cylinders and mine shaft, but no indication of either were found. Several ammunition pouches, bolts and bayonets were brought back and these establish identification of the 124th and 125th Regiment, XIII Corps.Footnote46

Following this patrol, the commanders had excellent clues as to the Germans’ intentions. The equipment made it possible to identify the unit and gave information on their armament. In short, in nine minutes, the men had gathered useful information for the intelligence officers. By July 2, seven other patrols were covering the 5th Brigade’s front line. The 22nd Battalion’s mission was to inspect enemy barbed wire and locate occupied trenches. No enemy was seen or even heard. The barbed wire was in very good condition, and a ditch filled with water, barbed wire, and pieces of wood with sharp iron spikes was spotted.Footnote47 In the early hours of the morning, the information was shared in the daily report.Footnote48

The men of the 2nd Division kept up this pace for the rest of July. It is difficult to assess the number of patrols deployed during this period, as war diaries often lack precision in this respect. Also, when it is stated that the entire front was patrolled, can we assume that the three Battalions occupying the Saint-Éloi line sent out at least one patrol? Therefore, the 5th Brigade, which covered this sector until July 14, sent out approximately thirty-two patrols.Footnote49 On July 15, the 4th Brigade took over in the Saint-Éloi sector. There is no mention of patrols in the war diary, but this does not mean that none were out. Examination of the documents also reveals that between July 1 and 15, 1916, in the same sector, the 5th Brigade carried out three raids, two on July 1 and one on July 3. The 4th Brigade attacked on July 20, 26, and 29.Footnote50

On July 3, four unoccupied, concrete-fortified machine-gun positions were observed, along with a sniper post, an observation post, and a communication trench. The coordinates of these significant features were identified, enabling the officers to annotate them on their maps of the region.Footnote51 The same was true on July 4, when a patrol from the 22nd Battalion visited a machinegun position that had been identified the previous night. This time the patrol was able to confirm that it had been damaged artillery fire. They reported that the enemy was extremely active, as several improvements had been made at another position. That same night, an 18th Battalion patrol attempted to destroy an observation post, but failed. They reported that the flanks of this post were very well defended.Footnote52 Once again, the very precise information required to establish level 2 situational awareness was gathered. This appears in intelligence report no. 273, but more interestingly, the information gathered on July 3 and 4 could be combined with that gathered by the other battalions on July 1. Also, the intelligence report dated July 16 refers to report no. 285 (July 15), indicating that new information had to be added concerning several enemy groups that had been engaged the previous night. One patrol reported that each group was in fact made up of a minimum of twenty soldiers and was armed with machine guns.Footnote53

On July 29, a raid was carried out by the 29th Battalion. Acquiring evidence of gas use was their objective. On their return, the men brought back precise information useful for maintaining situational awareness. According to the patrol, the enemy trenches were 8 feet deep and in splendid condition. Boxes of gas cylinders were indeed found at the scene, but no chemical weapons were spotted.Footnote54 For their part, the men of the 18th Battalion confirmed that they had covered an unoccupied 50-metre trench with no sign of chemical weapons. During the patrol, however, they heard what they confirmed to be a large group of enemy soldiers working on the support trenches.Footnote55 Indeed, the enemy was identified and the presence of gas weapons confirmed in the 18th Battalion’s sector, but much more information was gathered and reported to the chain of command for analysis and distribution.

The information gathered by different patrols in different areas was compiled and followed up. Gradually, the consolidation and sharing of intelligence created a more accurate picture of the overall operational situation. As a result, General Turner had much better level 2 situational awareness than when he arrived.

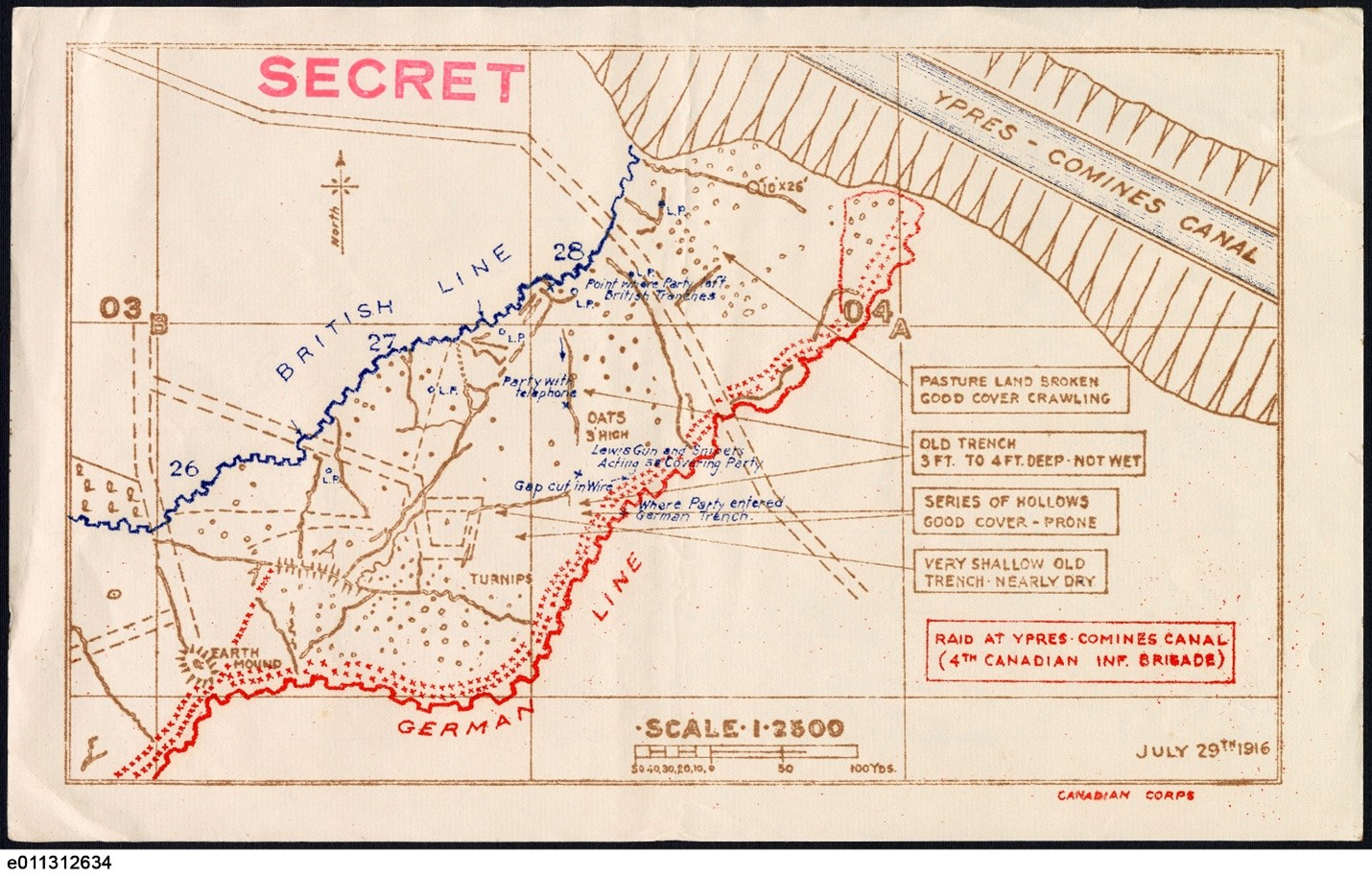

Gradually, 2nd Division headquarters had the information it needed to build up a credible picture of the operational situation on the Saint-Éloi front. This result, achieved through patrols and raids, now offered level 2 situational awareness, an asset that was non-existent in April and May. Topographic maps were a reliable reference and therefore essential in this respect for commanders. They were living documents, constantly being updated as patrols returned. When they had the time, the soldiers took the trouble to draw sketches to help clarify the information passed on to their superiors. In fact, many maps, such as the one in Figure 2, contained significant detail on the location and depth of rivers, lakes, or craters, the density of forests or vegetation in general, the condition of roads and railroads, etc. This information was essential for operations planning.Footnote56

Source: BAC, WD, “2nd Canadian Division, General Staff, 01-07-1916/31-07-1916.” Available at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca.

Click to enlarge imageFigure 2: Map of the Saint-Éloi sector, 2nd Division, July 29, 1916.

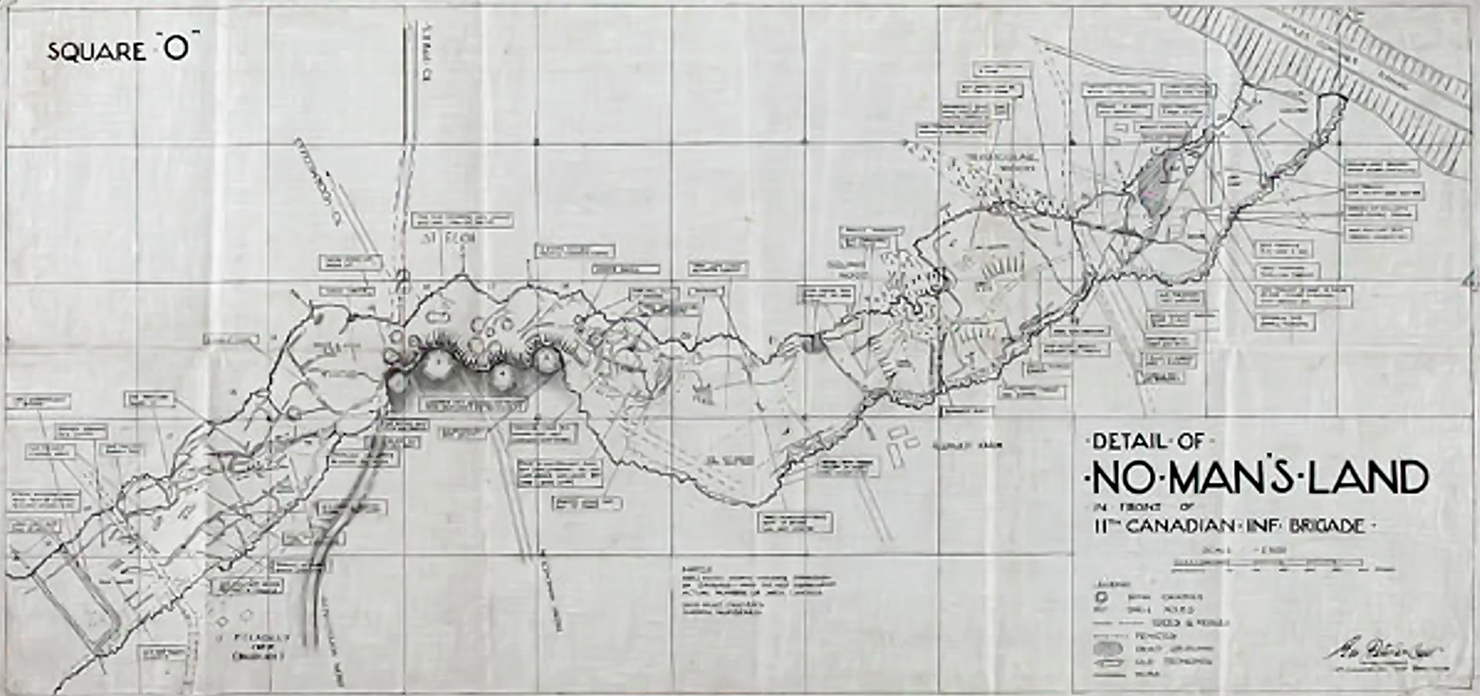

As the days and weeks went by, the maps became increasingly precise, like the one found in the 11th Brigade’s war diary (Figure 3). The information contained in the diary was so precise that it would have been impossible to obtain it by aerial reconnaissance alone. A closer look at the map shown in Figure 2 (2nd Division) and Figure 3 (11th Brigade) reveals that this is the same map that was handed over when the relief was carried out. Indeed, on August 25, the 11th Brigade took over the Saint-Éloi sector as the 2nd Division set off for the Somme. Five days later, the Canadian Corps relieved Anzac’s 1st Corps and moved into the Somme trenches.Footnote57

In conclusion, we can affirm that July was decisive for the 2nd Division. Soldiers and commanders had acquired combat experience that, while costly, was invaluable. In just a few weeks, they were able to regain the initiative. In fact, once the defensive positions had been consolidated, the soldiers embarked on a major intelligence-gathering exercise. Thanks to successful raids and patrols, situational awareness was improving day by day. The soldiers also worked extremely hard to maintain this situational awareness by confirming information previously gathered by other patrols. The war diaries and intelligence reports of July and August 1916 were also looking different from those of April and May.

Source: BAC, WD, “War diaries–11th Canadian Infantry Brigade. 1916/08/01–1916/11/30.” Available at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca.

Click to enlarge imageFigure 3: Map of the Saint-Éloi sector, 11th Brigade

CONCLUSION

The fighting in the Saint-Éloi sector was the baptism of fire for the soldiers of the 2nd Division. Because the relief operation had been carried out on too large a scale and without proper planning, the men arrived at Saint-Éloi with no information about the terrain or the enemy. Commanders found themselves technically blind, lacking sufficient intelligence to conduct operations with a good chance of subsequent success. If Canadian soldiers were to hold their position in the face of German counter-attacks, a long and arduous process of consolidation was necessary.

In July, the tide gradually turned. After consolidation, Canadian positions stabilized, allowing for a review of priorities. The battalions were able to organize and coordinate themselves for effective offensive operations. Soldiers could now start patrolling No Man’s Land again, attacking enemy trenches and feeding headquarters with their findings. Every night, several teams went out on patrol, bringing back new elements and confirming others. Gradually, officers at all levels as well as the troops gained continuous and complete situational awareness, enabling the Canadian Expeditionary Force to take the initiative in the sector.

From 1916 onwards, the air force flew more and more often, carrying out a wide range of missions. During reconnaissance flights, pilots and observers, with their admittedly rudimentary cameras, were able to provide an overview that enabled intelligence officers to map the front. However, the air force could not acquire and maintain situational awareness on its own. In fact, photographs were only a starting point. The information gathered through photos often had to be confirmed by men in the field. In this sense, raids and patrols proved highly effective. Our study of the Saint-Éloi front between April and August 1916 shows that raids and patrols played a key role in acquiring and maintaining situational awareness. The information gathered by the men on the ground and in the air, once analyzed, became real military intelligence, supporting the decision-making process of commanders at all levels. Leaving the Saint-Éloi sector for the Somme, the 2nd Division relieved the 11th Infantry Brigade in the proper manner, leaving them with a high degree of situational awareness.Footnote58