Photo: Cpl Nathan Moulton, Valcartier Imaging

Veterans, civilians and over 350 military personnel participate in a Remembrance Day ceremony at the Citadelle in Québec, Québec, November 11, 2016.

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) consists of the Regular Force (Regulars), Reserve Force (Reservists), and Special Force components. Reservists enroll in one of four subcomponents to perform dutyFootnote 1 through three classes of service as shown in Figure 1.Footnote 2 Compared to Regulars, Reservists typically have lower military pay and a variable frequency of military employment, relying to different degrees on civilian earnings.Footnote 3

| Primary Reserve (P Res) |

Canadian Rangers (Rangers) | Cadet Organizations Administration and Training Service (COATS) | Supplementary Reserve (Supp Res) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duty and training as may be required of them. | Duty and training as may be required but not annual training. | Supervision, administration, and training of cadets. | Not required to perform any military duty. | |

| Class A Service | Part-time service. | Part-time service. | Part-time service. | |

| Class B Service | Long- or short-term full-time temporary training or administrative service. | Long- or short-term full-time temporary training or administrative service. | Long- or short-term full-time temporary training or administrative service. | |

| Class C Service | Full-time service on a military operation. | Full-time service on a military operation. |

When service-related injuries prevent Reservists from civilian and military employment, they may seek financial compensation through four government programsFootnote 4: CAF Reserve Force Compensation benefitsFootnote 5; CAF Long Term Disability (LTD) insurance Footnote6; Government Employees Compensation Act benefitsFootnote 7; and VAC’s Income Replacement Benefit (IRB).Footnote 8 Each program has unique eligibility requirements, admissible injuries, duty circumstances, and scales of benefits. This article focuses on the IRB for eligible Veterans with service-related disabilities while enrolled in VAC’s medical, psychosocial, and vocational rehabilitation program.

Originally named the Earnings Loss Benefit (ELB) in the 2005 Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act (CFMVRCA), sometimes called the New Veterans Charter, the benefit was renamed the IRB with changes introduced through the 2019 Veterans Well-bring Act (VWA). The government’s objective for the IRB is to provide Veterans, “replacement income to relieve financial pressures … to successfully complete rehabilitation.”Footnote 9 Rehabilitation may take months or years and, if unachievable, the IRB will be provided for life.

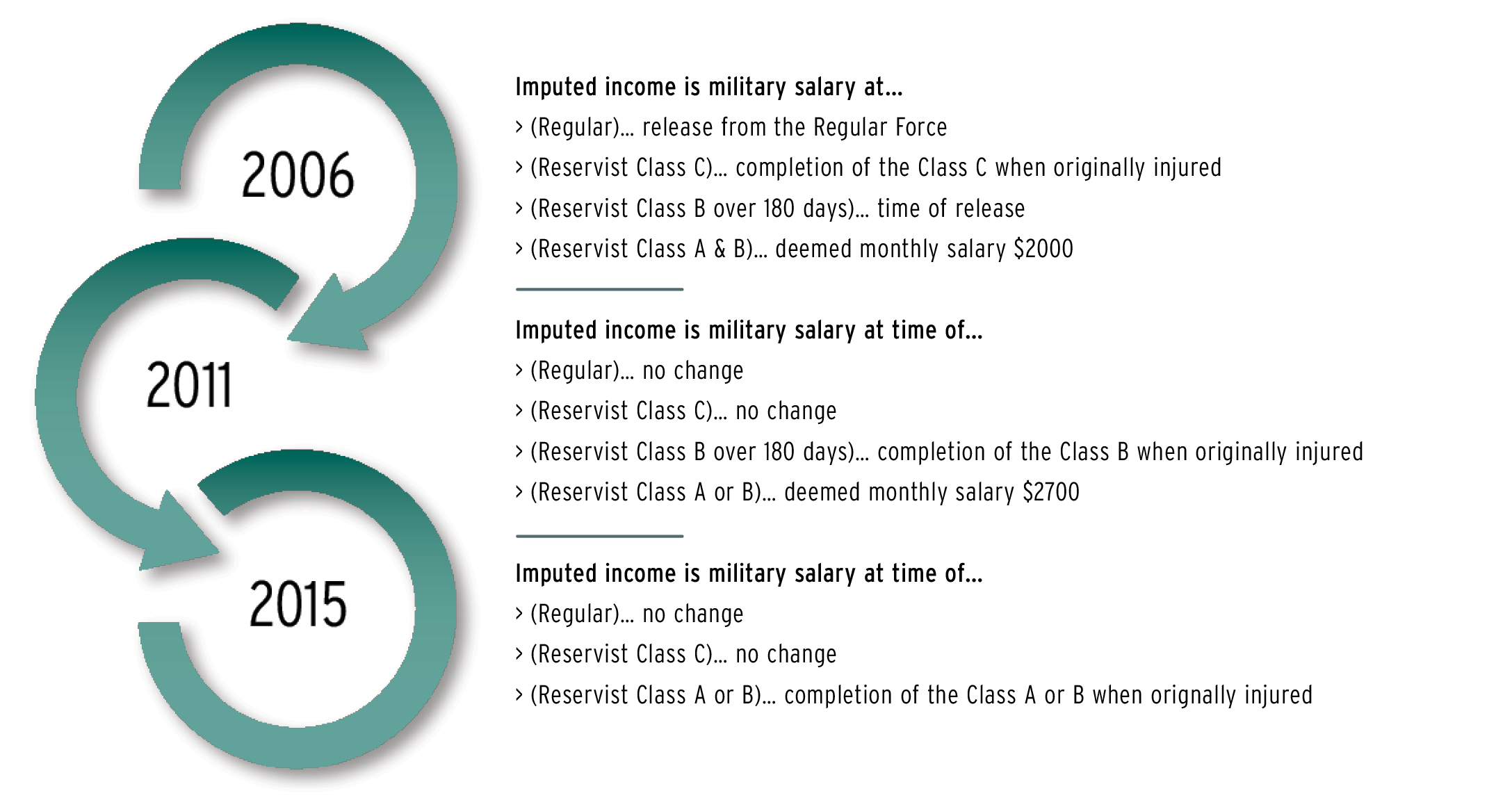

VAC determines the benefit using an “imputed income” formula defined in the Veterans Well-being Regulations (VWR).Footnote 10 While VAC’s website notes the IRB ensures “Veterans’ total income will be at least 90 percent of their gross pre-release military salary,” this is not the case for disabled Reserve Veterans.Footnote 11 Comprising 47% of CAF VeteransFootnote 12 and 17% of IRB recipients,Footnote 13 the imputed income for Reserve Veterans is defined as their military pay backdated to the “event that resulted in the … health problem.” First defined in 2006, subsequent changes are summarized in Figure 2. Despite Reservists relying to different degrees on civilian earnings, the imputed income is based solely on their military salary at the time of the injury, even if it is of a previous pay rate or rank. In 2015, a minimum amount payable for all Veterans was introduced, and in all versions, the benefit is adjusted annually for inflation. Noting that this method of IRB calculation can result in unfair outcomes for Reserve Veterans, in 2020 the Veterans Ombudsman cautioned of an “unconscious bias in favour of Regular Force Service as compared to Reserve Force ServiceFootnote 14; this echoed a similar 2013 Ombudsman’s report.Footnote 15

Figure 2: Summary of VWR Res F Veteran imputed income definitions

As the official newspaper of the Government of Canada, the Canada Gazette publishes new and proposed government regulations.Footnote 16 Prior to the 2006 regulations and for each amendment, it announced that modern disability management studies, research on successful transition, committees, organizations, and evaluations on gaps and improvements were used to develop the ELB.Footnote 17 As the Gazette claimed changes were made “in response to… VAC’s own research,”Footnote 18 this article reviews VAC’s research between 1992 and 2018 in order to determine how findings have been used to define “imputed income” for disabled Reserve Veterans.

METHODOLOGY

To examine the extent of VAC’s research related to income replacement for disabled Reserve Veterans, this article uses a four-stage methodological framework to identify relevant VAC publications. Publications are compared to legislation, regulations, and the corresponding Canada Gazette editions providing VWR background. It should be noted that the CFMVRCA and regulations were renamed the VWA and VWR in 2019, at which time the IRB replaced the ELB and other benefits. This article will use IRB to describe IRB or ELB.

Stage 1. Identifying the research question

This review examines the extent to which VAC research has informed the IRB imputed income to meet the government’s objective of relieving financial pressures for the study population of Reserve Veterans. Not defined in legislation or VAC’s policies, financial pressures in this article are defined as “threats to the Veteran’s financial well-being,” where financial well-being is defined by Skomorovsky et al. as the “state where one can fulfill current and ongoing financial obligations, have a sense of financial security, and is able to make choices that allow enjoyment of life.”Footnote 19 As the IRB supports disabled Veterans undergoing military to civilian transition, this article uses the CAF’s definition of transition, that is, “the period of reintegration from military to civilian life and the corresponding process of change that a serving member/Veteran and their family undertake when their service is completed.”Footnote 20

Stage 2. Identifying relevant studies and documents

VAC’s Annotated Bibliography of VAC Research Directorate Publications for 1992–2018 (Annotated Bibliography)Footnote 21 lists “all of the English reports”Footnote 22 and presents 161 publications which provide “sound scientific evidence” informing VAC policies, programs, and services; twelve additional research publications were retrieved from the VAC Research Directorate website.Footnote 23 Of these, 123 were available in full or as abstracts at websites of the VAC Research Directorate, Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research, the Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, and the Veterans and Families Research Hub. For the remaining publications, the Annotated Bibliography provided 50-word citations. Current and past versions of the CFMVRCA, VWA, and VWR were available at the Department of Justice website and the Canada Gazette was retrieved from www.canadagazette.gc.ca.

The VAC-CAF Advisory Council’s 2004 report, The Origins and Evolution of Veterans Benefits in Canada 1914-2004, Footnote 24 with forward by Peter Neary, helps frame the introduction of the 2005 CFMVRCA. In addition to VAC research publications, L. Williams and J. Anderson’s, The unique financial situation of a Primary Reservist: Satisfaction with compensation and benefits and its impact on retention,Footnote 25 presents a picture of the Reservist’s mix of civilian and military earnings, while the Auditor General of Canada’s 2016 report on the Canadian Army ReserveFootnote 26 helps to understand physical risks inherent in Reserve service.

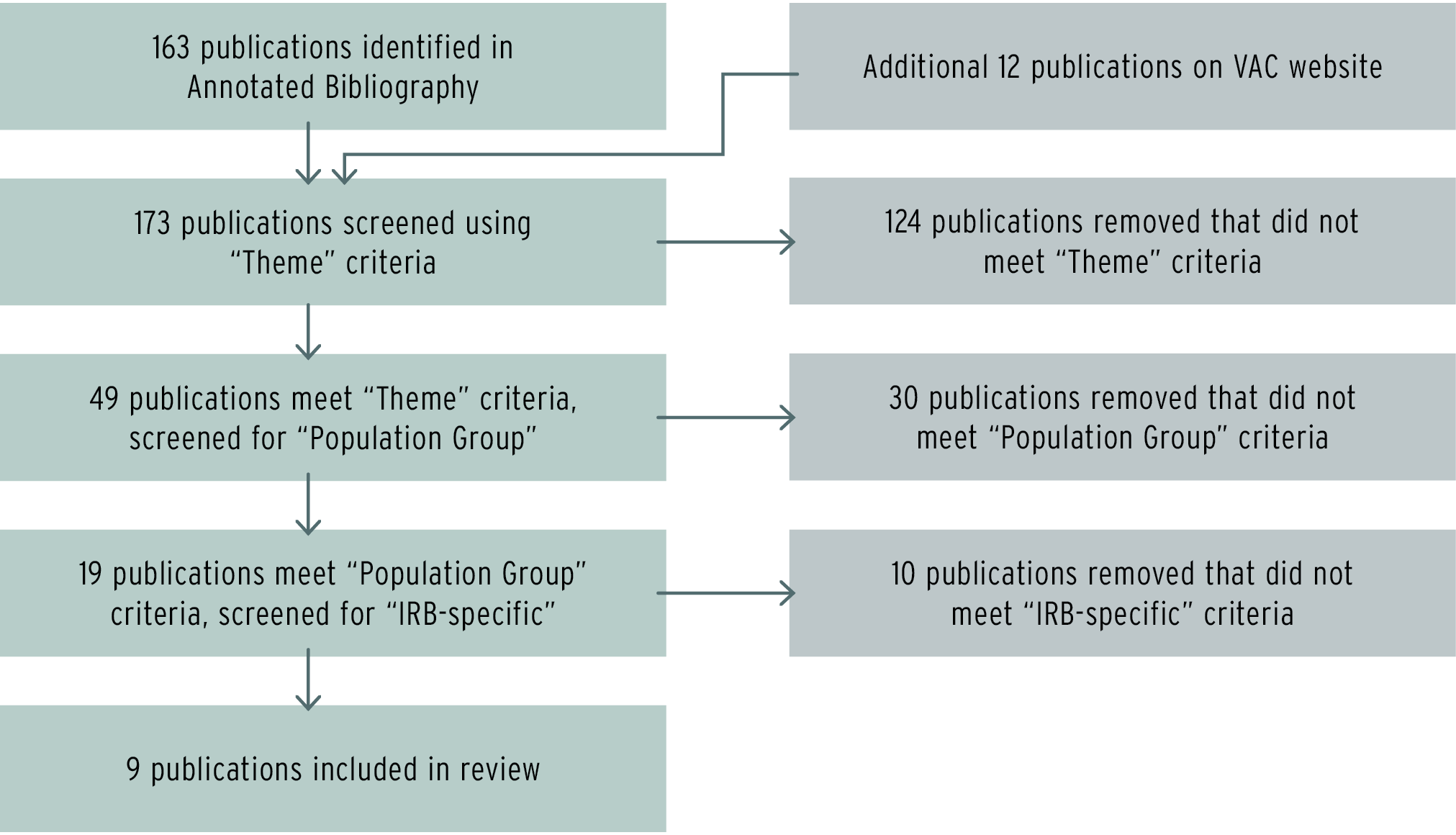

Stage 3. Study selection

The 173 publications were reviewed using the theme of “Transition,” including topics such as military to civilian transition, post-release rehabilitation, compensation, pre- and post-release financial health, and life after service; Figure 3 illustrates that 49 publications met the “Transition” theme. “Population Group,” was assessed to determine research related to Reserve Veterans or all Veterans, resulting in 19 publications meeting “Transition” and “Population” criteria. These were reviewed for IRB-specific criteria, such as financial well-being, employment, and income issues, with nine meeting the full scoping criteria; eight concerned all Veterans and one exclusively studied Reserve Veterans.

Figure 3 – Process to select relevant VAC research publications

Stage 4. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The selected publications are listed in Table 1. Each was reviewed in detail and the findings are discussed in the Results section.

| TITLE | AUTHORS | DATE |

|---|---|---|

| CAF clients of VAC: Risk factors for post-release socioeconomic well-being | Marshall and Matteo | 2004 |

| The origins and evolution of Veterans benefits in Canada 1914–2004 | VAC-CAF Advisory Council | 2004 |

| Work-related experience and financial security of VAC clients | Marshall et al. (1) | 2005 |

| Post-military experiences of VAC clients: the need for military release readiness | Marshall et al. (2) | 2005 |

| Pre- and post-release income: Life After Service Studies | Maclean et al. | 2014 |

| 2013 synthesis of Life After Service Studies | Van Til, et al. | 2014 |

| Income adequacy and employment outcomes of the New Veterans Charter | Maclean, et al. | 2014 |

| Veterans of the Reserve Force: Life After Service Studies 2013 | Van Til, et al | 2016 |

| Income recovery after participation in the rehabilitation program | Maclean and Poirier | 2016 |

| Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 5 Canadian Army Reserve — National Defence | Auditor General of Canada | 2016 |

| Veterans’ identities and well-being in transition to civilian life | Thompson et al. | 2017 |

| The unique financial situation of a Primary Reservist: satisfaction with compensation and benefits and its impact on retention | Williams and Anderson | 2020 |

Photo: Corporal Djalma Vuong-De Ramos, Canadian Armed Forces photo

Reservists of 14 Military Police Platoon, 12 Military Police Platoon and regular force members of 1 Military Police Regiment conduct a C8 rifle range at 3rd Canadian Division Forces Base Edmonton Detachment Wainwright, March 9, 2021.

RESULTS

Categorizing, grouping, and measuring Reserve service

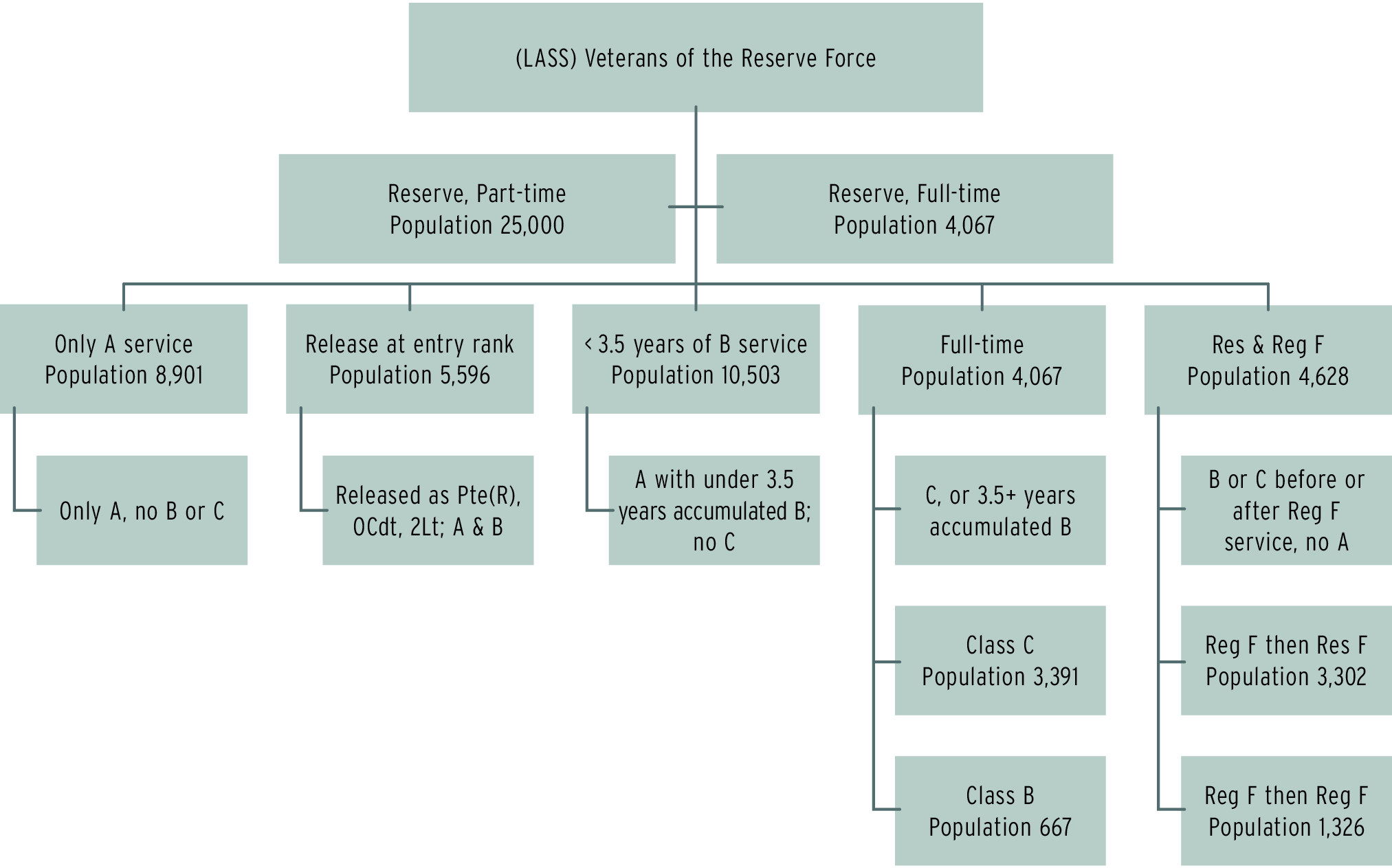

Reserve data is grouped five ways for the nine selected publications, as shown in Figure 4. In contrast, Regular Veterans are normally analyzed as a homogenous population. Publications from the Life After Service Studies (LASS) are highlighted by an asterisk (*) and will be discussed separately.

| Reserve Service Grouping for Analysis | VAC Research Publication Title |

|---|---|

| Five groups based on class of service |

|

| Two groups based on class of service |

|

| Reservists as a uniform block |

|

| Part- and Full-time Reservists |

|

| Refers to all of CAF |

|

VAC research prior to the 2006 imputed income

Painting a “complex picture of … post-discharge work and income security,” Marshall et al. (2), found “the need for finely tuned policy initiatives to enhance … economic security” for disabled Veterans.Footnote 27 Marshall et al. (1) determined that those releasedmedically are “in jeopardy of economic difficulties upon release due to early and unexpected discharge.”Footnote 28

To “place the case for renewal squarely on the public agenda,” the VAC-CAF Advisory Council prepared a 163-page report in 2004 on the evolution of Veterans benefits in Canada. Recognizing contemporary CAF members and Veterans as a client group with complex needs, the report outlined recommendations for programs supporting military to civilian transition and ongoing care of those injured. It noted that in 1976 Primary Reservists became eligible for CAF LTD insurance if released due to injuries sustained during military operations; eligibility was expanded in the 1990s to include all service-related injuries. For Reservists disabled on part-time service, the benefit was 75% of $2,000 per month, regardless of military rank or actual lost income.

Two 1997 CAF studies, J.W. Stow’s A Study of the Treatment of Members Released from the CF on Medical Grounds, and R.G. MacLellan’s Care of Injured Personnel and the Families Review: A Final Report, were highlighted by the Advisory Group report. Interviewing exclusively Regular Veterans, Stow made 15 recommendations concerning administration of medically released personnel and improving access to and relevance of post-release benefits, arguing for “a source of income to bridge the gap between one career and the next.”Footnote 29 MacLellan confirmed this and included Reservists in the following investigation. Outlining problems gaining access to medical care, MacLennan noted that “obtaining appropriate compensation for lost civilian income was also a major concern” of Reservists.Footnote 30

Promising financial pressures would be minimized by the IRB “to enhance the opportunity for successful rehabilitation,” the 2006 Canada Gazette announced the benefit will “mirror” the existing CAF LTD insurance program.Footnote 31 While disabled Regular Veterans would receive 75% of their salary at release regardless of when the injury occurred, the benefit for similarly disabled Reserve Veterans injured on part-time service would be 75% of an imputed income of $2,000 per month. While the imputed income definitions reflected a “finely tuned policy,” the 2006 IRB only addressed the “jeopardy of economic difficulties” for disabled Regular Veterans.

VAC research supporting the 2011 release

Prior to 2011, VAC released nine research publications concerning the transition of Regular Veterans. The 2011 Gazette announcement mentions that “many (unnamed) studies” supported the IRB being based on 75% of the greater of Veterans’ military salary at release (for Regular Veterans) or a new minimum pre-tax annual income of $40,000. The new minimum income was justified by quoting research by Statistics Canada and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC)Footnote 32 defining a “low-income cutoff” wage at $37,000 annually; this research was not applied to disabled Reserve Veterans injured on part-time duty, whose benefit was 75% of the deemed monthly salary of $2,700, or $24,300 annually. Although the Gazette notes that “certain reservists” are at the highest risk of receiving insufficient “financial support required to meet basic needs,” the benefit for those injured on long-term full-time service was reduced from being 75% of the military salary at release to 75% of their salary when originally injured.

The Life After Service Study (LASS) program and Reserve Veterans

To better understand the transition and health of Veterans, VAC, CAF, and Statistics Canada conducted the LASS program in 2010, 2013, and 2016.Footnote 33 Although Reserve Veterans comprise 47% of CAF Veterans, they were studied only in LASS 2013.Footnote 34 In 2010, Reservists were not included as “data was not available in time for the … start date,”Footnote 35 while no reason was given for 2016.Footnote 36 LASS was also conducted in 2019 for Regular Veterans only.

VAC’s Annotated Bibliography lists 32 LASS publications. Five from LASS 2013 met this article’s criteria, of which Veterans of the Reserve ForceFootnote 37 is the sole publication focused on Reserve Veterans. It organizes Reserve Veteran data into five population groups based on “discriminating military characteristics,” as shown in Figure 5. These are based on the classes of service illustrated in Figure 1. LASS 2013 methodology excluded the data of 8,900 Reserve Veterans with exclusively Class A (part-time) service due to “administrative data” deficienciesFootnote 38 and subsequently excluded the data of 5,600 Reservists released in their “entry rank.”Footnote 39 The remaining data is a reasonable pool of Reserve Veterans with service characterized by administration, local training, formal courses, long-term employment, and operational deployments.

Figure 5: Reserve groups in Veterans of the Reserve Force study

Counting heads versus using full-time equivalents

S. Tucker and A. Keefe’s 2019 Report on work fatality and injury rates in Canada recommends using full-time equivalents (FTE) in assessing workplace injury compensation systems to reflect, “the estimated total number of employees covered by a compensation board … as opposed to the total number of people employed in a jurisdiction.”Footnote 40 The groups in Figure 5 represent “people employed in a jurisdiction” and not the full-time equivalents.

Table 2 summarizes characteristics, demographics, and transition data from LASS 2013. If Reservists from the “<3.5 years of B service” group work one evening per week (one half-day’s duty) and certain weekends, and attend summer courses lasting several weeks, they will be on duty approximately 60 days a year. Regulars and full-time Reservists spend 220 days per year on duty when weekends, holidays, special leaves (e.g., statutory holidays, sick leave), and vacation time are excluded. While Table 2 measures “Length of service” in years enrolled, the annual paid days for the “<3.5 years of B service” group may be 25% to 33% of the duty year for full-time Reservists and Regulars. If compared using full-time equivalents, the 2% VAC client percentage for the “<3.5 years of B service” group would approach 6% to 8%.

| Only A service | Release at entry rank | < 3.5 years of B service | Full-time | Res & Reg F | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Primary Reservists | 8,901 | 5,569 | 10,503 | 4,067 | 4,628 | 33,668 |

| % of total | 26% | 17% | 31% | 12% | 14% | 100% |

| VAC Clients | 53 | 56 | 210 | 691 | 1,527 | 2,538 |

| % of group | 0.6% | 1% | 2% | 17% | 33% | 8% |

| Length of Service | ||||||

| Less than 10 years | 8,723 | 5,458 | 8,717 | 1,423 | 1,574 | 25,895 |

| % of group | 98% | 98% | 83% | 35% | 34% | 77% |

| 10 to 19 years | 89 | 56 | 1,260 | 1,708 | 370 | 3,483 |

| % of group | 1% | 1% | 12% | 42% | 8% | 10% |

| 20+ years | 89 | 56 | 420 | 895 | 2,684 | 4,144 |

| % of group | 1% | 1% | 4% | 22% | 58% | 12% |

| Age at Release | ||||||

| Under 30 years old | 7,655 | 4,845 | 8,297 | 1,423 | 1,064 | 23,285 |

| % of group | 86% | 87% | 79% | 35% | 23% | 69% |

| 30+ years old | 1,246 | 724 | 2,206 | 2,644 | 3,564 | 10,383 |

| % of group | 14% | 13% | 21% | 65% | 77% | 31% |

| Reason for Release | ||||||

| Involuntary | 1,691 | 1,225 | 1,891 | 407 | 324 | 5,538 |

| % of group | 19% | 22% | 18% | 10% | 7% | 16% |

| Medical | 0 | 56 | 210 | 569 | 509 | 1,344 |

| % of group | 0% | 1% | 2% | 14% | 11% | 4% |

| Voluntary | 7,121 | 4,232 | 8,087 | 2,806 | 3,332 | 25,579 |

| % of group | 80% | 76% | 77% | 69% | 72% | 76% |

| Retirement Age | 0 | 0 | 210 | 244 | 463 | 917 |

| % of group | 0% | 0% | 2% | 6% | 10% | 3% |

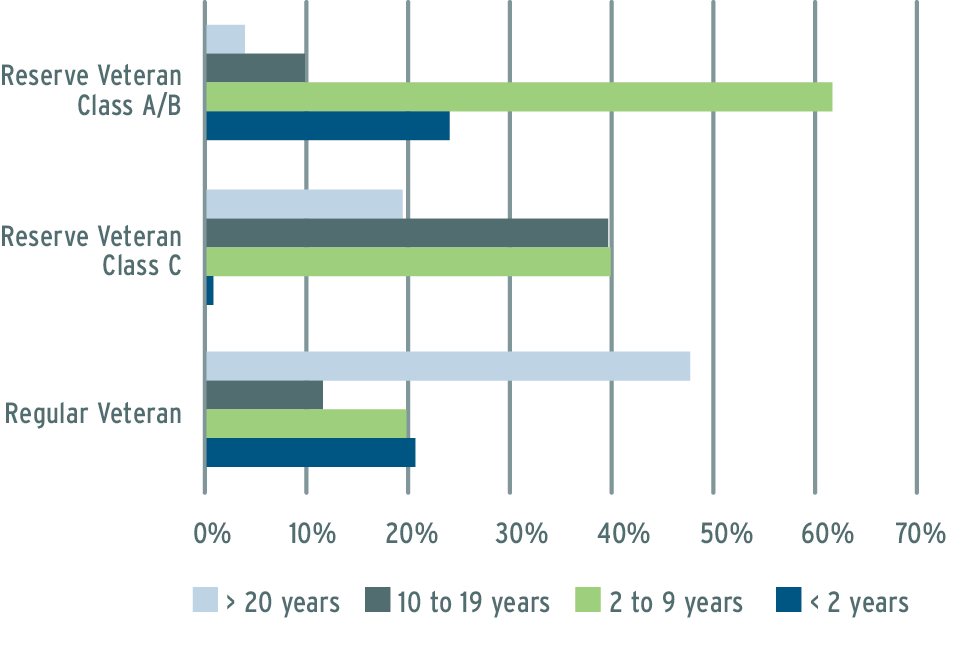

Using LASS 2013 data, Figure 6 illustrates that close to 50% of Regulars served 20 or more years before release, 95% of Class A/B Reservists served less than 20 years, and over 80% of Reservists with Class C service served under 20 years. While it may appear that Reservists face less risk of injury than Regulars, VAC client percentages for Reserve Veterans are lower than Regular Veterans because they are on duty less frequently (60 days versus 220 days) over a shorter career (95% below 20 years versus 50% over 20 years). Indeed, the Auditor General of Canada’s 2016 report found that the differences in training between Regulars and Primary Reservists “increase the risks of injury to soldiers when they train or deploy.”Footnote 41

Figure 6: Comparing length of service of Regular and Reserve Veterans

Grouping Class C service

As shown in Figure 5 and Table 2, LASS 2013 publications group Reservists having “any Class C service” together with those having “more than 3.5 years of Class B service” with the rationale that these groups show similarities in “age of release” and “adjustment to civilian life.”Footnote 42 Using information from Veterans of the Reserve Force, Table 3 presents these characteristics plus three others. Those with Class C service are more closely aligned with the “<3.5 years of Class B service” group in being from a combat arms occupation in the Army and, perhaps more importantly, in post-service employment. This is likely due to Class C service being performed for limited full-time periods by typically part-time Reservists, who then return to part-time service. Periods of Class C service range from a few weeks (e.g., flood response) to six to twelve months (e.g., deployment to Afghanistan), and, as the study notes, the average accumulated Class C service over a career is 0.9 years.Footnote 43

| Characteristics | > 3.5-year Class B service | Class C service of any length | < 3.5-year Class B service |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 2 years service | 0% | 0% | 13% |

| > 20 years service | 32% | 20% | 4% |

| Easy adjustment to civilian life | 49%* | 61% | 76% |

| Combat arms | 19% | 45% | 62% |

| Army | 52% | 80% | 87% |

| Post-release employment rate | 65% | 80% | 84% |

* The LASS study advises that this number is unreliable due to small sample size

Regular and Reserve service

The “Res & Reg F” group includes Veterans who served as Regulars then Reservists or vice versa. Of the former Regulars who became Reservists, 81% served over 20 years as Regulars before becoming Reservists. On average, they served 2.4 years on Class B service and 1.3 years on Class C service before their final release at an average age of 46 years. LASS 2013 does not advise on the length of their Reserve service, but given their average release age and length of Regular service beforehand, their time as Reservists was probably relatively short.

Revised military characteristics

By moving Reserve Veterans with Class C service into the “<3.5- year Class B” group and removing the Veterans whose final release was from the Regular Force, the Table 2 information changes as shown in Table 4. With this, the “<3.5 years of B service” group’s VAC client percentage becomes 5%. If this group predominantly performs 60 duty days annually over their career, with periods on Class C (total average 0.9 years) and Class B service (total average 0.5 years), the VAC client percentage in a full-time equivalent system would be 15% to 20%. With the adjustments of Class C service and former Regulars released as Reservists, Table 4 demonstrates that 87.5% of 32,342 Reservists are employed in a predominantly part-time model.

| Only A Service | Release at Entry Rank | < 3.5 Years of B Service | Full-time | Reg Released as Reservist | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Primary Reservists | 8,901 | 5,569 | 13,894 | 676 | 3,302 | 32,342 |

| % of Primary Reserve | 28% | 17% | 43% | 2% | 10% | 100% |

| VAC Clients | 53 | 56 | 717 | 169 | 1,090 | 2,085 |

| % of Group | 1% | 1% | 5% | 25% | 33% | 6% |

| Adjusted for Full-time Equivalents | 4% | 4% | 15%-20% | 25% | 33% |

Reservists released at the age of 30 and older are three times more likely to have Class C service and four times more likely to be a VAC client, as shown in Table 5. This older group tends to have higher pre-release civilian earnings, and, as VAC clients, are twice as likely to fall below the low-income measure.

| Characteristics | Released 29 and younger (<29) | Released 30 and older (30+) |

|---|---|---|

| % Reserve Veterans | 75% | 25% |

| Served Class C | 10% | 33% |

| % VAC Clients | 20% | 80% |

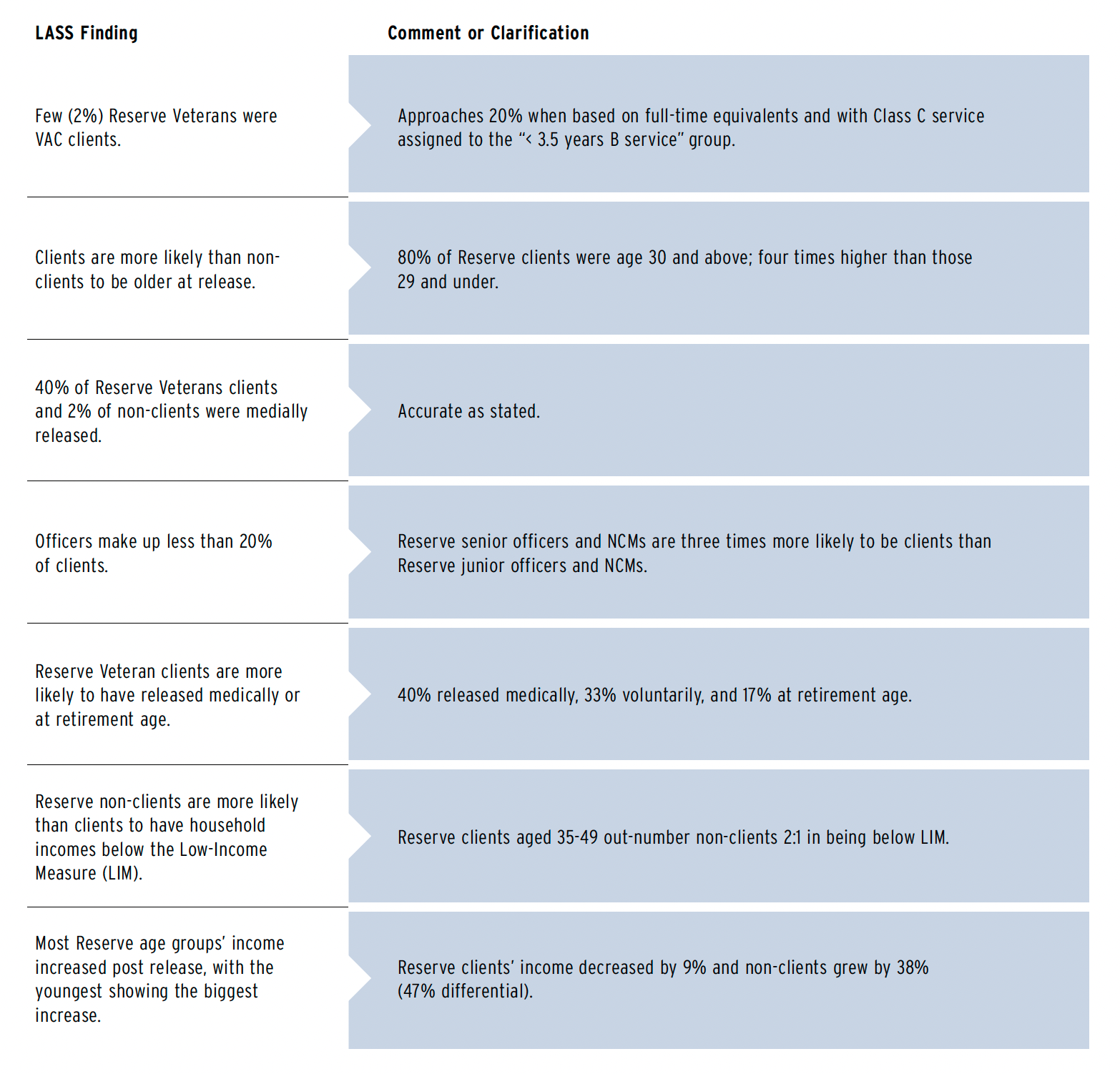

Summary of LASS finding with adjustments

A summary of existing LASS findings, with adjustments and comments, is provided in Figure 7. When viewed from a fulltime equivalent perspective and regrouping the Class C service with the otherwise part-time group, the perspective that “few” Reserve Veterans become VAC clients is adjusted. Reservists who are over 30 years old at release come into focus as a small population with a higher risk of service-related injury that is more exposed to fall below the “low-income measure.”

Photo: Cpl Myki Poirier-Joyal

Reservists from Montreal Territorial Battalion Group participate in winter warfare training in Laval, Quebec during Exercise QUORUM NORDIQUE on January 23, 2016.

Figure 7: Summary of Reserve Veteran findings from LASS 2013

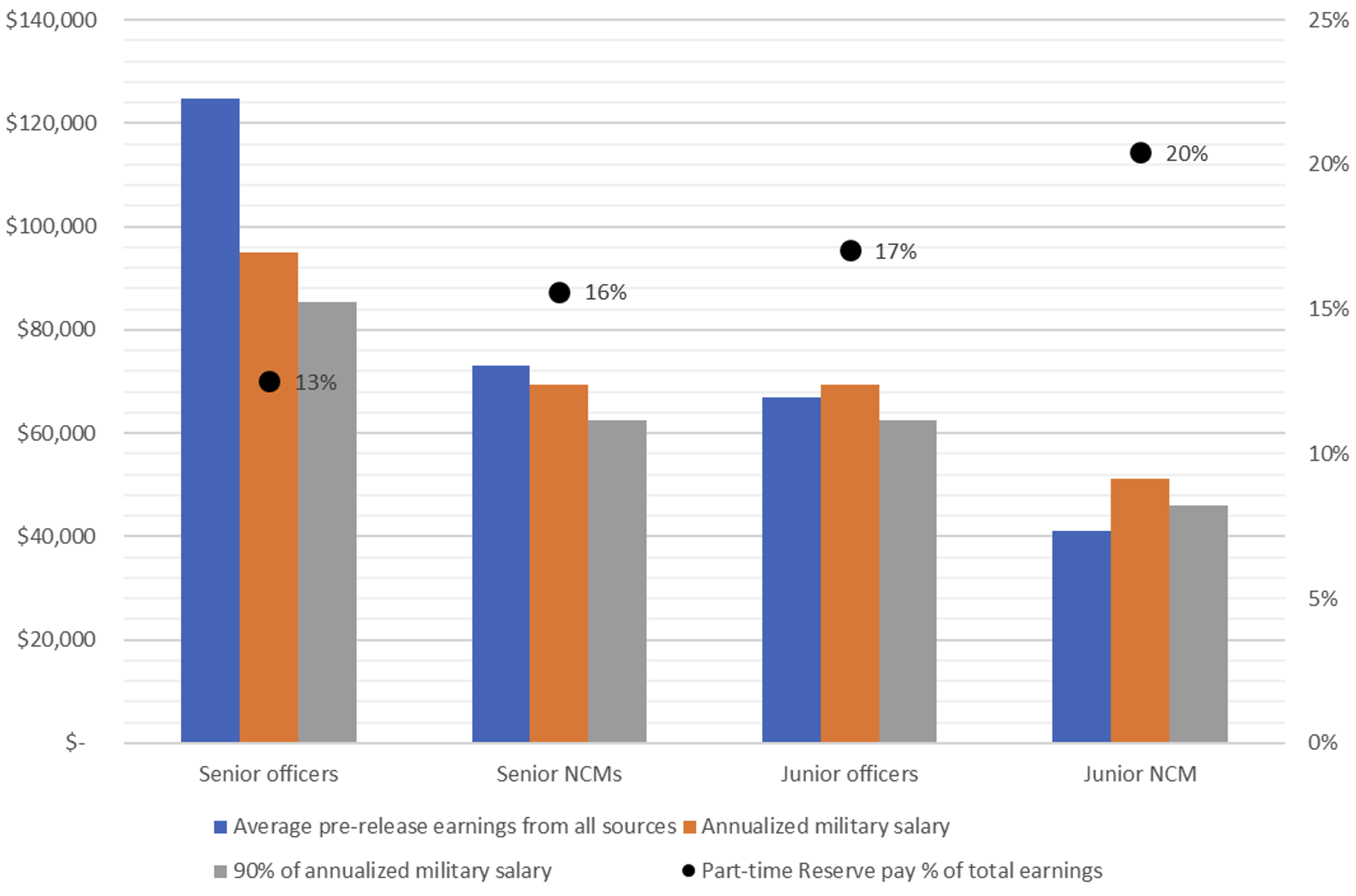

Additional Reserve Veteran findings can be derived from LASS reports related to Reservist average pre-release total earnings, including civilian earnings, based on income tax information. Using LASS 2013 dataFootnote 44 and an average 2014 daily Reservist pay rate for each rank groupFootnote 45, Figure 8 illustrates civilian and military earnings for part-time Res F Veterans.Footnote 46 As part-time Reservists progress in rank, the military portion of their total earnings decrease from 17% to 13% for officers and 20% to 16% for NCMs. With progress in rank, their yearly civilian income tends to exceed the annualized military salary which would be used to determine IRB if they were unable to work due to a service-related disability.

Figure 8: Reservist civilian and military earnings

VAC research supporting the 2015 amendment

The Canada Gazette preceding the 2015 VWR amendment listed VAC’s own research and evaluations, committees, organizations, and the Veterans Ombudsman as identifying areas for IRB improvement.Footnote 47 As shown in Figure 2, the 2015 VWR amendment changed the imputed income for Reserve Veterans injured on Class A or any Class B service from the deemed salary approach to be the imputed military salary at the time of the injury. While this was an improvement for part-time Reservists, the new method did not reflect the LASS 2013 findings.

In the context of the 2015 change, the Gazette claims the Veteran’s Ombudsman recommended that Reserve Veterans injured on part-time service receive the same income support as those injured on “full-time” Reserve service. The Ombudsman report actually recommends using the “same salary level as that used to calculate the benefit for full-time Reserve Force and Regular Force Veterans.”Footnote 48 Similarly, the Gazette advises that a “similar sentiment was echoed” by the parliamentary Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs; the Committee’s report states that all disabled Veterans must “be entitled to the same benefits … whether they are former members of the Reserve Force or of the Regular Force.”Footnote 49

VAC research supporting the 2019 VWR amendment

As outlined in Veterans’ Identities and Well-being in Transition to Civilian Life, military-civilian transition is one of life’s most intense transitions, bringing significant identity challenges that is further exacerbated by chronic health problems or being forced to leave.Footnote 50 Part-time Reservists have “hybrid identities” and need a “coherent personal narrative that integrates both lives to prevent identity crises.” Facing identity reconstruction issues if they lose their civilian employment returning from military operations, they will also emerge with the loss of civilian employment due to a service-related disability. Many identities are simultaneously challenged for disabled Reserve Veterans, including their civilian earning potential, civilian profession, and ability to sustain financial well-being.

Changes made in the 2019 VWR reflected the creation of the IRB to replace five benefits, including ELB, and the increase of the benefit to 90% of the imputed income. The definitions of the imputed income remained unchanged.

Unique financial situation of a Primary Reservist

Released in 2020, William and Anderson’s The unique financial situation of a Primary Reservist: Satisfaction with compensation and benefits and its impact on retention examines Reservist reliance on military income and its relationship with civilian earnings. It provides an understanding of potential financial pressures inherent in using an annualized military salary as the IRB’s imputed income.Footnote 51 In response to the question, “How necessary is your income as a Reservist to your current household financial situation?” as many as one third of Reservists, predominantly Class A, see their military salary as completely, or fairly, unnecessary to their financial situation, or “without it my life wouldn’t change at all.” This cohort of Reservists are predominantly in the aged 30 years and older group, which makes up 80% of Reserve VAC clients. If disabled by a service-related injury, these Reservists would be most at risk of IRB not relieving financial pressures.

Calculating the IRB by using an imputed income backdated to time of the injury or the time of Regular Force release creates a different risk for longer-term full-time Reserve Veterans and the ex-Regulars whose final release is as a Reservist. Their benefit would be calculated using a potentially lower rank or salary, e.g., releasing as a Sergeant and receiving compensation based on a Corporal’s salary from the time of the original injury. When the 33% whose military salary is unnecessary to their financial situation is combined with the 12% who release as full-time Reservists or ex-Regulars, close to one half of Reservists are at risk of receiving an IRB insufficient to relieve financial pressures.

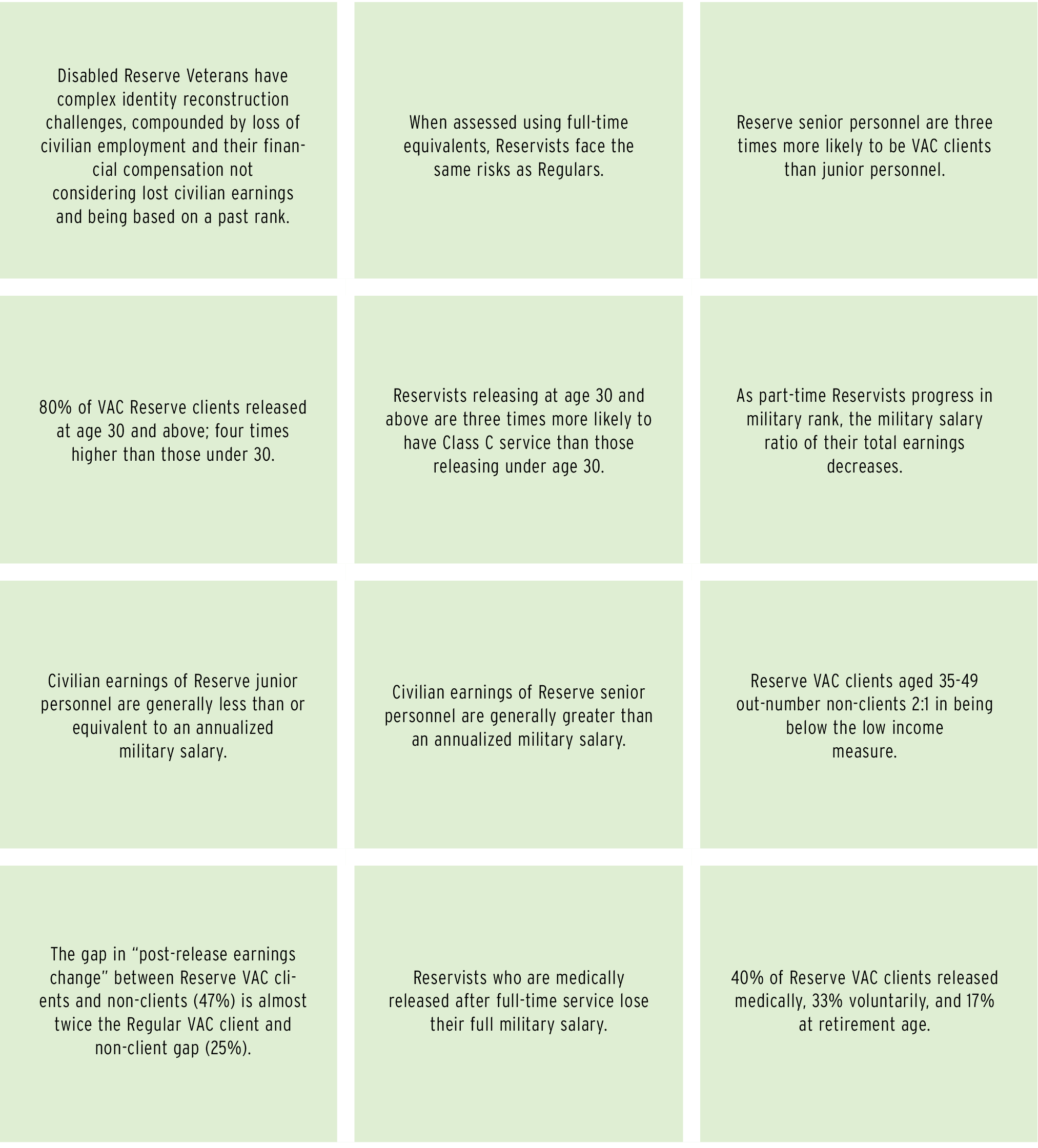

Evidence-based findings for Reserve Veteran IRB

Figure 9 illustrates the twelve major findings from the nine VAC research publications selected to reflect compensation and military-civilian transition of disabled Reserve Veterans; the findings show this article’s adjustments. An income replacement benefit to relieve financial pressures of disabled Reserve Veterans and their families participating in the VAC rehabilitation program should address these evidence-based findings

Photo: 32 Canadian Brigade Group Public Affairs

Canadian Army reservists from 4th Canadian Division medical units unload a simulated casualty from a CH-146 Griffon helicopter during Exercise STALWART GUARDIAN on August 21, 2015 at Garrison Petawawa, Ontario.

Figure 9: VAC research evidence-based findings for Reserve Veteran IRB

DISCUSSION

VAC research and IRB for Reserve Veterans

Of the 173 VAC research publications released between 1992 and 2018, only one is dedicated to analyzing Reserve Veterans. This publication and eight others provide evidence-based findings which should inform compensation and military-civilian transition policies of Reservists with service-related disabilities.

Prior to the introduction of the New Veterans Charter, VAC research identified that those released medically face economic jeopardy and called for initiatives to enhance economic security. Further, the VAC-CAF Advisory Council reported that a major concern of injured Reservists was obtaining appropriate compensation for lost civilian income. Despite this, the 2006 method to calculate IRB “mirrored” the CAF LTD insurance. The 2011 method was unchanged for those injured on Class C service, reduced the benefit for those injured on longer-term Class B service, and offered a slight benefit increase for those injured on part-time service. No VAC research supported these changes, and HRSDC research supporting the new Regular Veteran minimum benefit was disregarded in the case of Reservists.

In 2015, the method to calculate IRB for Reservists was standardized and based on the individual’s military salary at the time of the disabling injury. The justification provided in the Canada Gazette misstated recommendations made by the Veterans Ombudsman and the Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs. Despite claiming VAC’s own research identified “areas for IRB improvement,” the changed benefit did not reflect findings in the LASS 2013 publications.

Analyzing Reserve Veteran data

Regular Force service is a single period beginning at enrollment and ending at release while Reservists conduct distinct periods of service, or classes, from enrollment until release. Therefore, the administration of Reservists provides a granularity of records that is not available for Regulars. While this granularity presents opportunities to examine various scenarios, it creates issues when comparing publications, e.g., the nine VAC research publications chosen for this article had five different Reserve groupings. Even the five LASS 2013 documents reviewed used three methods to group Reservists.

Grouping of Reservist data should be based on a development and employment model where Reservists generally perform part-time Class A service of local administration and training, interrupted by periods of full-time Class B service for training and full-time Class C service for military operations, all with a background of full-time civilian enterprise. This applies to 87.5% of Reservists (Table 4) with exceptions being Reservists fulfilling full-time long-term Class B service. When measuring injury and compensation rates, analysis of Reservists must be sensitive to full-time equivalents of “duty” when compared to Regulars, public servants, or other groups of Reservists.

The current imputed income definition is partially satisfactory

As currently defined, the IRB would meet its objective for 20% of Reserve VAC clients: those released at age 29 and younger. For the 80% released at age 30 and older, their financial pressures are less likely to be relieved as the IRB considers only the military salary backdated to the time of the injury with no consideration of actual earnings lost.

An evidence-based and equitable imputed income definition for disabled Reserve Veterans would reflect the findings from this article. A possible evidence-based imputed income definition which meets the government’s objective for IRB would be: “Imputed income will be the greater of the highest of annual taxable earnings from all sources over the five years before their release, their annualized military salary at release, or the monthly minimum amount.” This definition would apply equally to disabled Regular Veterans.

CONCLUSION

The IRB for Reserve Veterans is not based on VAC’s own research. Unlike the assurance Regulars and their families have, it would be coincidental if a Reserve Veteran’s financial compensation for a service-related disability or death relieves their family’s financial pressures and meets the government’s stated objective of the IRB.

Sufficient evidence-based research exists to formulate the IRB for Reserve Veterans. However, care must be taken in future research in reflecting a more realistic grouping of Reserve data and in applying full-time equivalences where appropriate. Total lost earnings of Reservists and the consequences to their family’s standard of living must be considered, especially for those who serve Canada longer, have more days on duty, are more likely to have served in operations, and are more likely to be VAC clients. While Reservists may serve on a part-time basis, the consequences of a service-related disability can be full-time and lifelong.