Photo: Master Corporal True-dee McCarthy, Canadian Forces Combat Camera

Member of the Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC) speaks during the Rehearsal of Concept (ROC) drill on April 3, 2020 in preparation to deploy Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel under Operation LASER in response to COVID-19.

Lieutenant-Colonel Kelley joined the reserves in 2004 while finishing his BASc at the University of Waterloo. In 2006, he transferred to the regular force and finished basic training. He served as an engineer intelligence officer for the headquarters of Joint Task Force Kandahar for two years, of which 10 months were spent deployed to Afghanistan. Subsequently, in 2009, Captain Kelley was stationed in England to complete his master’s degree in Geospatial Intelligence with the British Army. After serving as second in command of the Geospatial Information and Services Squadron of the Mapping and Charting Establishment, he deployed to Haiti with Op HAMLET to the Mission des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en Haiti (MINUSTAH) while posted to 5 RGC. He commanded the CF School of Military Mapping before moving on to the Army HQ as lead planner for Exercise ARDENT DEFENDER, where he planned and managed realistic, level 5 counter-IED training involving over 30 nations and all tiers of government from municipal to the UN. In 2019, he was awarded the Master of Defence Studies by RMC, returned to MCE as DCO, and then spent one year as the Executive Assistant to the Canadian Military Representative to NATO. He has just returned from that task, promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, to work as the Assistant Chief Military Engineer for the Canadian Armed Forces.

Diversity in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and particularly diversity among its senior leaders are critical topics today. There are many sources of diversity and today’s topical issues are gender and race. However, in selecting its General and Flag Officers (GOFOs), the CAF lacks diversity in another area as well, and it is one over which it has much more control: the military experience of those selected to join the ranks of GOFOs. Because GOFOs are divorced from their entry trade when they are promoted to their first star, there is no simple way to measure what trades are represented in what proportion among the senior leadership. However, when carefully counted, it is clear that certain military trades are disproportionately represented among GOFOs compared to the number of subalterns they intake. Understanding which trades are overrepresented and what CAF doctrine says about grooming senior leaders allows comparison with allies, the private sector, and the civilian public sector. This sheds light on changes that might help to improve diversity among the CAF’s GOFOs.

Diversity of trade of origin matters for the same reasons as diversity of gender, race, or other factors. In particular, it brings two things: a larger pool of candidates and a broader perspective among incumbents. If talented and capable young people with the potential to become key leaders in the institution happened to have a passion for training and became personnel selection officers, they would have almost no chance of bringing those aptitudes to bear on behalf of the CAF; their candidacy for strategic leadership positions is erased by the lack of diversity in the GOFO corps in terms of trade of origin. Likewise, different backgrounds bring different perspectives to the institution’s strategic problems and this applies to trade background as well as more fundamental background characteristics like race or gender.

Representation of the Trades Among GOFOs

Most officers in the CAF intuit that certain trades are disproportionately represented among GOFOs. They see the many infantry, armoured, pilot, and naval warfare officers among GOFOs and conclude that being one of these “operator” trades greatly increases one’s chance to join the most senior levels of the CAF. However, many members of the operator trades remark that they are more numerous than most trades and are therefore simply represented in proportion to the size of their trades. This is not the case.

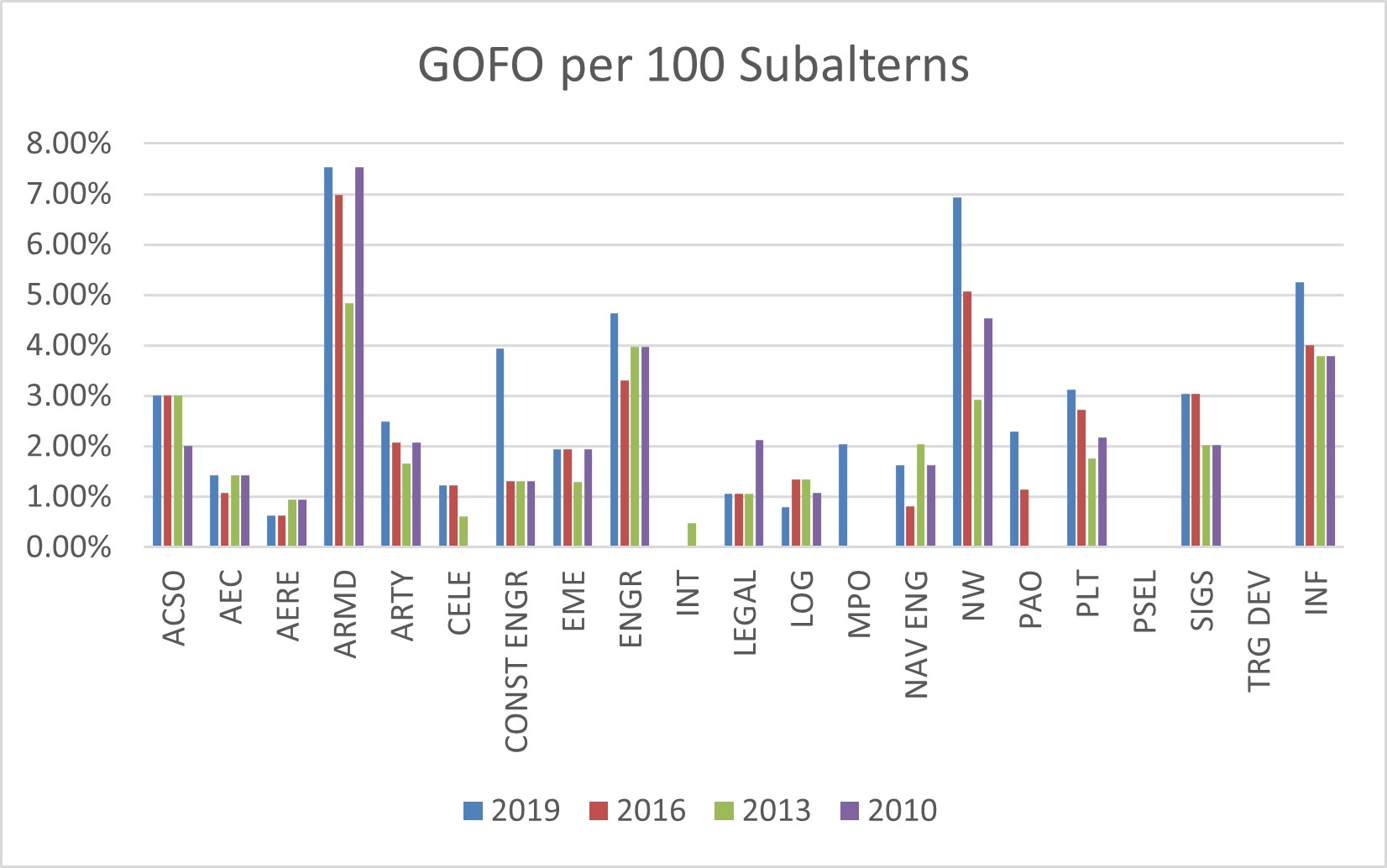

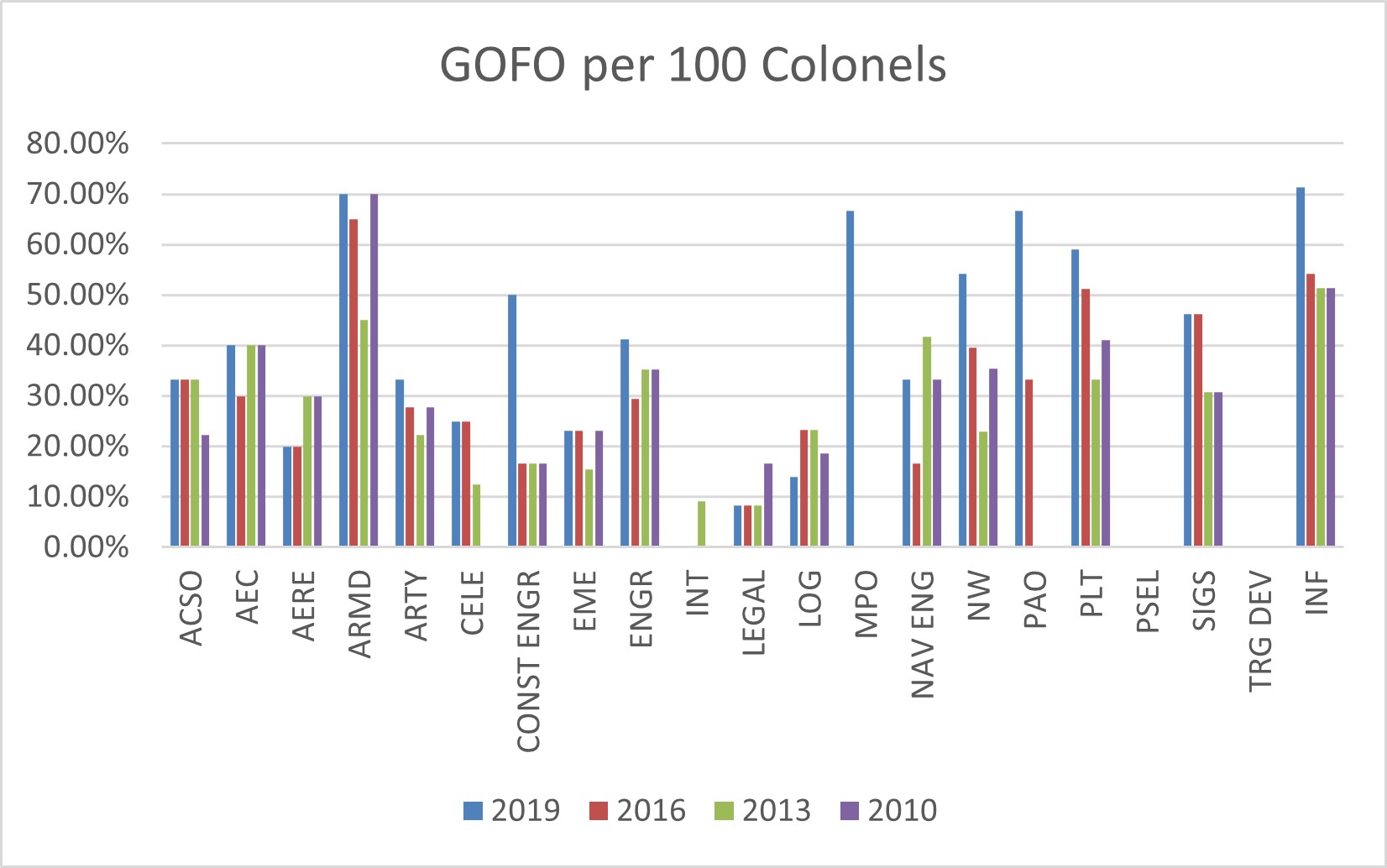

In 2020, the author, as a student at the Canadian Forces College, completed a Defence Research Paper in which he enumerated GOFOs over sample years for the preceding decade. Comparing the trades of origin of GOFOs to the Chief of Military Personnel production figuresFootnote 1 for 2019 provided an estimate of the proportion of subalterns from each trade who go on to become generals. While not a perfect estimate as the number of subalterns in a trade may have changed in the decades between recruitment of the current GOFOs and 2019, it provides a reasonable approximation. This approximation is supported by the fact that the conversion rates for colonels into GOFOs generally resembles those for subalterns. While there are some improvements possible in the method used, the sensitivity analysis conducted showed the results to be relatively insensitive to errors of the scale introduced by the method’s weaknesses.

Photo: Corporal Lynette Ai Dang, eFP BG Latvia Imagery Technician, Canadian Armed Forces Photo

A Canadian Armed Forces member of NATO enhanced Forward Presence Battle Group Latvia stands ready on a presence patrol in a Light Armoured Vehicle 6.0 during Operation FORTRESS in Viļāni, Latvia on 19 September, 2023

An officer who wants to be a GOFO should join the armoured corps. In 2019 there were 7.5 generals with an armoured background for every 100 subalterns in that trade. There were 14 armoured GOFOs for 20 armoured colonels (equivalent to 70 GOFOs for every 100 colonels). The average for non-medical and non-chaplain trades (excluded because of their special status in CAF doctrineFootnote 2) was 2.5 GOFOs per 100 subalterns and 40 GOFOs per 100 colonel/captain (Navy). These numbers fluctuate with the number of GOFOs in the CAF, which increased by over 20 between the 2016 and 2019 samples but remain proportionate in all the sampled years. Sampling every three years was chosen for a 9-year period based on the availability of data which was increasingly limited going further back in time. It is possible that longer-term cycles are in play and that further research is warranted, but for now, these trends provide a starting point to review the impact of trade on advancement as the CAF looks more closely at GOFO selection and advancement. See Figures 1 and 2 for a graphical presentation of these data.

Naval warfare officers and infantry officers were the next most likely subalterns to become GOFOs, and infantry officers had 71.5 colonels per 100 generals. These outcomes were consistent across the decade surveyed. Exceptionally, in 2019, Public Affairs Officers and Military Police Officers were tied for 3rd place in conversions from colonel/captain (Navy) to GOFO with 67 per 100; this is a function of the law of small numbers because there were 3 colonels/captains (Navy) and 2 GOFOs in that year but that was not repeated in other years surveyed. Both trades were near but below the CAF average for GOFOs per 100 subalterns. Pilots were also consistently likely to advance from colonel to general, but because of the very large number of subaltern pilots, they were around the CAF average for converting subalterns to GOFOs.

Even clearer than the winners are the losers. In the decade studied, no Personnel Selection or Training Development officer was made a GOFO. Between the two trades, there were 160 subalterns in 2019; the 186 subalterns in the armoured officer trade had 14 generals that year. This partly reflects the narrowing of the trade, with only 1 colonel/captain (Navy) each compared to the 20 colonels for the armoured corps. However, the Intelligence Corps, with 11 colonels/captains (Navy) also had no GOFOs in 2019 and only 1 in the decade studied. The logistics branch, with the most subalterns at 746 and the second most colonels/captains (Navy) at 43 had 6 GOFOs in 2019; in other words, less than half as many GOFOs created from more than twice as many colonels/captains (Navy) as the armoured corps.

Canadian Doctrine on the Matter

Canadian doctrine is clear that this is not what is supposed to happen. The seminal doctrine for the training and development of officers is found in the Report of the Officer Development Board, commonly known as the Rowley Report, written by MGen Roger Rowley in 1969. Three key ideas from this document remain guiding principles for officer development today. First, the concept of development periods, which direct different skill development at different stages of the officer’s career. Second, the emphasis on education over training, which dictates the approach to officer development at Canadian Forces College. Finally, it dictates a balanced approach to development with trade-specific, elemental, and joint requirements, as well as a balance between technical and human leadership for successful officer development.Footnote 3

Rowley dictates an egalitarian approach to officer selection and development, which he traces to the Prussian Government of 1808: “The only title to an officer’s commission shall be, in times of peace, education and professional knowledge … all individuals who possess these qualities are eligible for the highest military posts.”Footnote 4 Rowley wrote in an era when technical mastery was emerging as a critical aptitude for warfighting and he showed foresight in identifying the need for officers versed in communication, logistics, acquisitions, and combat support. This led to his vision of the ideal general officer: someone with a general aptitude for the organization’s function and specialized knowledge of key emerging technologies and problems.Footnote 5

Rowley does not dismiss the importance of an officer’s background trade, although he specifies that it becomes decreasingly relevant as the officer progress through the ranks. For example, he does not contend that the commander of the Air Force could just as easily be a combat engineer as a pilot. Further, he notes that certain highly specialized positions require very precise background experience, such as the Judge Advocate General, which calls for a legal background. Rather, his interpretation is a warning against over-specifying the background required to hold many senior positions.Footnote 6

The question of which positions require what degree of specialization is a key issue of contention. While a professional background in medicine or law is a clear prerequisite for the Surgeon General or the Judge Advocate General, there is decreasing clarity about when a specialist versus a generalist is required as you go through the professions. Does the provost marshal need a police background? Does the commander of the CAF cyber force need a cyber background? Does the commander of Canadian Forces Intelligence Command need an intelligence background? Major Brent Robart argues for the specialty of cyber command in his paper, “Leadership Requirements in Emerging Domains of Operations.”Footnote 7 Rear Admiral Bishop argued that, since four of five intelligence chiefs among the five-eye intelligence partnership in 2019 did not have an intelligence-specific background, a specialist was not required to lead intelligence.Footnote 8 There is no clear consensus in the CAF for when a specialist background is needed for a GOFO, when an operator background is required, and when a generalist is most suited.

Rowley’s work was followed in 2008 by the CF Executive Development Program concept by LGen (Ret) Michael Jeffery.Footnote 9 Jeffery’s primary source was a series of interviews with contemporary GOFOs as well as some training and professional education specialists. His analysis to some extent reflects the view of the incumbent GOFOs that the current system is effective, but they recognize, as he does, that there is room for improvement. Jeffery’s primary concern, based on these interviews, is the lack of expertise. GOFOs in his study had the experience and knowledge to lead operationally, but they lacked contextual exposure to handle the “complexities of Ottawa.” He recommends exposure to an international and political/military interface as part of the preparation for advancing to the strategic level. While this would not be uniquely solved by recruiting from the supporting trades into the GOFO cadres, many of them are more exposed to the civilian components of DND and to partners than the operator trades.

Similarly, most of Jeffery’s other concerns about the 2008 GOFO corps could be interpreted to partly stem from the nature of the experience of the operator trade alumni, who typically hold primacy at the tactical levels and may therefore not develop the same skills for compromise and adaptation that are needed at the strategic level, when defence is only a component of the government’s security approach. He specifically notes that “the cultural bias within the CF is that our primary mission is operations, so every opportunity must be taken to be in operations.”Footnote 10 He goes on to acknowledge that the consequence is an operationally astute GOFO corps with strategic weak points. Although the details of Jeffery’s report focus on the design of professional development to address these concerns, the context setting shows the problems and successes of the current model and suggests the potential for diversification of trade to address some of his identified gaps.

The latest work on the topic, the Officer Developmental Periods 4/5: Project Strategic Leader reportFootnote 11 from 2014, starts by confirming that the concerns raised by Jeffery remained relevant at that time, as did the fundamental theory articulated by Rowley. One of its key conclusions was that “what got us here is not going to get us there,” reaffirming the need to break out of the approach which has been inherited from the successes of the Second World War. It goes on to describe five interconnected “domains of employment” for GOFOs: machinery of government; socio-political milieu; domestic and international operations; the profession of arms; and the business of defence. It acknowledges that different GOFO positions needed different mixes of these aptitudes. These positions are divided into Force Employment; Force Generation; Force Development; National Security Professional; and Strategic Systems. Chief of Military Personnel is an example of Strategic Systems; National Security Professionals are the senior advisors, liaisons, and related roles for GOFOs. Looking at the five domains across the five roles, the conclusion is that all GOFOs need some ability in all domains and in all roles—a conclusion echoed ubiquitously that generals are ultimately generalists. However, it places the emphasis on Force Generation and Force Development, which favours the current model for training and employing operator trades. This conclusion indicates that support trades would need to retain a connection to CAF soldier and equipment basics in order to be effective GOFOs; full specialists would lack the required generalized aptitudes revealed in the study.

Overall, Canadian doctrine has not addressed military trade specifically, except for Rowley’s rejection of it as a relevant criterion for advancement at the higher levels. However, subsequent reviews to Rowley’s have found gaps in the operational focus of the strategic leadership, which may be partly due to the preference for operator trades and the specific military experience which accompanies them. Other nations have looked at the problem as well and reached similar conclusions.

Allied Thought on the Matter

The process and criteria for selecting GOFOs are not a matter of academic research for most of Canada’s allies. However, for the United States (US), and particularly the US Army, it is. Although the US Army is not an ideal model for the CAF due to its vastly different scale and culture, it can provide general insights into the leadership of soldiers and the management of large organizations.

Journalist Thomas Ricks analyzed the management of US Army generals from the Second World War to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in his comprehensive work “The Generals.” Philosophically, the US Army sees generals as generalists, like the CAF, and independent of trade of origin, but in practice they are not. In the Second World War, 59% of US Army generals emerged from the infantry branch.Footnote 12 This was proportionate to the other combat arms, including artillery and engineering, but it was twice as many as would have been expected if the non-medical supporting arms (mainly logistics) had been represented proportionately.Footnote 13

Photo: MCpl Jennifer Kusche, Canadian Forces Combat Camera

Military task force leaders from several NATO countries, including Canada, Czech Republic, Germany, Latvia and the United States, attend an exercise planning brief in the Hohenfels Training Area, Germany on Exercise ALLIED SPIRIT VI during Operation REASSURANCE on March 18, 2017.

One of Ricks’ key findings was that combat leadership experience produced successful generals in combat. This was consistently the case with division and higher commanders in the Second World War, where those with combat experience at the battalion and brigade levels were more successful at higher levels. However, it remained valid through Korea, Vietnam, and even up to General Petraeus in Iraq.Footnote 14 Petraeus was also cited as considering combat experience a key aptitude in selecting colonels for promotion. This may reflect the Project Strategic Leader report’s finding of the importance of Force Generation and Force Development for all strategic positions.

This perspective was echoed by a surprising source: Lieutenant-General Pagonis who commanded the logistics effort in support of the first Gulf War. He was an army logistician but credited his experience commanding an infantry platoon as a lieutenant in Cold War Germany, as well as his time supporting artillery in Vietnam, with his capability to support operations including leading logistics in the Gulf.Footnote 15 Pagonis’ technical knowledge was essential to his role, but his generalist knowledge and combat experience enabled him to successfully link in with the perspectives and requirements of the operational and tactical commanders of that theatre.

Modern thinking in the US calls for the explicit recognition of a seemingly similar distinction. The Centre for New American Security, a US defence think tank, published a report entitled, “Building Better Generals.”Footnote 16 The core proposition of this report was to explicitly stream US GOFOs into operational or enterprise roles. Division commanders, the commander of the Army or the Chair of the Joint Chiefs, among others, would be operational and these would draw from the operator trades primarily. The deputies, the support service commanders, and others would be in the enterprise stream. The argument is that such streaming from the rank of colonel and up would enable education to be tailored towards the chosen role and deepen experience since a GOFO would not need both operational and enterprise experience at each rank to be seen as ready to advance. This approach has not been endorsed officially by the Department of Defense, but similar ideas are common when discussing this problem in both Canada and the US.

In the Ministry of Defence (MOD) of the United Kingdom, thinking that mirrors Robart’s is emerging. Captain Parker, Royal Engineer, developed a similar thesis about a Jack of All Trades and the leadership of different trades.Footnote 17 He follows Robart’s logic that specialized domains, particularly those which are rapidly evolving, require specialist leaders to keep up, even though more stable domains benefit from generalist leaders. He notes that emotional intelligence is more important for strategic leadership than either technical or generalist experience, but given comparable candidates, specialists are needed in some strategic roles. Like the CAF, the MOD struggles to generate sufficiently specialized leaders, especially in technical fields. Parker recommends various ways of cross-pollinating the defence leadership with specialist leaders developed in the private and civilian public spheres.

Civilian Perspectives and Experience

The questions of specialist and trade background are closely related but not identical. However, the civilian world has no concept of trade in the way that the military does, at least not at higher levels. Consequently, background and level of specialization are useful proxies. The study of both private and public employment models provides some insight.

In the private sector, research is focused on Chief Executive Officers (CEO), but not on the senior executives who support them. This may raise the question of its applicability to selecting GOFOs that are not the most senior. University of Windsor scholar Eahab Eslaid conducted a study similar to the author’s Defence Research study but focused on CEOs rather than GOFOs. Elsaid classifies backgrounds into four categories: founder, output, throughput, and peripheral.Footnote 18 He defines an output background as related to the external links of the organization, like marketing and sales. The throughput group are engineers and operations planners who manage the core business of the firm. The peripheral group includes accountants and lawyers who provide specialized support. Founders are a unique category of CEOs who originally established the corporation and have special personal and emotional ties to it; their unique connection to the firm has no parallel in modern western militaries.

The throughput group corresponds closely to the operator trades who conduct the core business of controlled application of violence. The specialist groups are similar to the CAF’s specialized trades who bring vital but non-core skills to enable throughput. In the CAF, the output function is not filled by trades but by individuals from the operator or support groups who are temporarily assigned to output-oriented tasks like recruitment or policy. This is an important link to Jeffery’s perspective that officers should be exposed to exterior organizations, as part of their more junior development, to prepare them for later employment at the strategic level.Footnote 19 Given this correspondence between Elsaid’s research and the military question of the impact of trade on GOFO selection, his results are worth reviewing.

Elsaid’s most profound discovery was that companies consistently hire CEOs with similar background to their predecessors when things are going well. Engineers are replaced by engineers, lawyers by lawyers, etc. This is not the case when things go poorly; often the CEO is replaced by someone with a different background, usually a specialist with accounting expertise when finances are an issue or a lawyer when legal problems are the key concern. This finding implies that the CAF may be led by operator trades because they were the right choice in the Second World War, which is why similar leaders were selected and encouraged to replace them.

Elsaid’s research does show some reasons why operators might be the best choice for leading the CAF, but only generally. He found that companies focused on throughput activities like research and development tend to prefer CEOs with throughput backgrounds. If the Department of National Defence (DND) is the nexus for administration, support, finance, and management, it may be logical to view the CAF as the operational arm of DND and therefore having operators as its leaders might make a great deal of sense when the influence of the civilian aspects of the Department is factored in.

Research into the recruitment of senior public sector executives provides less understanding of why but important insights into how it is done. In Canada, public servant positions are tied to a list of experience, knowledge, and competency requirements. These requirements are subject to universal scrutiny, so individuals who want the positions can work towards meeting the requirements as much in advance as desired. Further, the requirements are subject to review and dispute in the long term, so a prerequisite of operator experience in a position can be argued against and established as necessary (or not) by open debate, rather than by the existing (operator dominated) power base. The importance of mentorship and grooming of senior leaders in preparation for assuming the most senior positions cannot be overlooked, but it can be included in the requirements.

A study of the effectiveness of this approach was conducted by Sakinah in Indonesia. Historically, Indonesia’s hierarchical public service filled vacancies above the entry-level by promotion of a subordinate of the vacant position.Footnote 20 The study tracked outcomes of a pilot group that applied South Korean approaches to public service hiring, which were broadly similar to Canadian approaches: competency requirements were defined for each position, and all applicants were invited to compete for the position against those requirements. The study revealed a significant increase in employee mobility in the bureaucracy and expected longer-term results to show improved outcomes. The brief description Sakinah provides suggests that the Indonesian process is similar to the CAF hierarchical model, while the South Korean approach advocated resembles the Canadian Public Service approach, at least as it is set out formally.

Review of Possible Courses of Action

The data are very clear that an individual’s trade has a direct and significant impact on an individual’s likelihood to become a GOFO. There are a variety of explanations that combine to explain why that is. Is the status quo a problem? If a change needs to be made, then three options are presented by this research: the Barno model which streams GOFOs into operational and support categories; the Pagonis model which emphasizes cross-training, especially for support trades; and the Public Service Model which defines the competencies required for all positions and allows everyone to compete to best satisfy these requirements.

Barno et al.’s idea of grouping US military generals into operational and support categories and assigning positions to each of them is a popular one. It is an intuitive approach to the problem based on the analogy to the practice used at lower ranks of grouping different specialties to different positions. This course of action should be avoided without extremely careful study. Among the senior officers interviewed regarding this research, this was the point raised most consistently by each of them: the CAF is small enough to manage each GOFO and each GOFO position individually; categorizing them ties the hands of our planners and administrators without promising any better results.Footnote 21 Representatives of support trades including logistics and intelligence, which might be among the most disadvantaged by the current system, agreed with GOFOs from operator backgrounds that this was the wrong way to approach the problem. This is further emphasized by the conclusions of Project Strategic Leader which notes five different fields of GOFO employment and nuances between positions in those fields.Footnote 22

The approach proposed by Pagonis is better but can be challenging in cultural and practical terms. Practically speaking, given the number of extra-regimental duties required of CAF officers, if one platoon in every battalion were reserved for command by a support trade captain to gain experience as Pagonis did, there might not be enough infantry captains to fill the extra-regimental duties expected (as that would represent about a 10% decrease in infantry production). More importantly, without additional training, could that support trade officer meet the expectations of commanding officers and the troops under their command? Even additional training for the CAF’s junior support trade officers seems impractical, and giving them easier jobs than their peers would negate the effectiveness of this proposed method.

The idea of promoting CAF advancement through applications rather than attrition, as the Public Service does, deserves to be investigated in greater detail than has been the case to date. It may make sense to spell out the required competencies for each position and then open them up to applications from any trade or even beyond the military. This certainly follows Parker’s logic of opening the doors to expertise gained outside of uniform.Footnote 23 In other words, would someone who had been a reserve infantry company commander and was now a CEO of a major tech company be a better commander of CAF cyber forces than a recent mechanized brigade commander? Maybe. This approach requires a more detailed investigation.

Barring the idea of looking more closely into a competency-based and application-oriented public service model for advancement, what is left to the CAF is the status quo. The status quo is working. The CAF continues to succeed in operations and to support its personnel. General Gosselin makes the key point that the current practice of selecting GOFOs based on experience and suitability for the duties of a particular task is working.Footnote 24 However, it is logical that having the most potential candidates for those positions will produce a better average outcome. Preventing someone with leadership qualities, emotional intelligence, and overall aptitude from advancing to the most senior ranks because they were interested in signals, logistics, or another support trade is not an optimal way to ensure that the CAF has the best leaders available.

The status quo can be modified very slightly to significantly reduce the incidence of that undesirable outcome. The change required is slight, but it is deadlocked between two factors: the CAF culture does not trust support trades to lead operational issues, and the support trades lack the experience to lead operational issues. Each of these problems prevents the other from being solved; an interventionist approach is needed to break the deadlock.

Recommendation

The CAF should review the merit of a competency-based and application-managed advancement process similar to that of the Public Service. There may be reasons why it may not be viable, but since none were discovered in this study it may warrant further exploration.

In the interim, the CAF can take specific action to improve the status quo without major upheaval in the personnel management approaches and philosophies that are currently proving effective. To enable the best candidates to be available for selection into GOFO ranks, the CAF must identify positions with an operational command nature, but without specific requirements for particular operator trade training or experience, and then ensure that support trade personnel are given those jobs. Support trade managers must identify and select members of their trades to fill those positions; those selected must have the potential for leadership and advancement in generalist roles.

Once good leaders with support backgrounds are being developed into generalist leaders through this program, there will be evidence generated to show the effectiveness of support trade leaders in operational roles, thereby challenging the present culture which denies this possibility. Eroding the culture that precludes support specialists from leading operational issues will open new positions for leadership-capable support specialists whose successes will further erode the adverse culture and cyclically break the deadlock.

The soldiers of the CAF deserve the best possible GOFOs. The best system must not exclude those with the talent and aptitudes to be GOFOs from reaching that rank because they were denied the experience necessary to hone those talents. The current system does exactly this to those who begin their careers in support trades. Simple changes can break the cycle which perpetuates this situation.

Photo: S1 Zach Barr, Canadian Armed Forces photo

A member of the British Armed Forces listens for orders after looking through a window for enemy positions during a simulated attack in the Rocky Ford Urban Training Area, during Exercise MAPLE RESOLVE in Wainwright, Alberta on May 15, 2022.