Photo: Corporal Eric Greico, Canadian Armed Forces Photo

The former Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) General Wayne Eyre, CMM, MSC, CD speaks with soldiers deployed on Operation UNIFIER-UK on October 28, 2022 in the United Kingdom.

Gen Eyre joined Army Cadets at age 12 and has been in uniform ever since. Gen Eyre attended Royal Roads Military College Victoria and Royal Military College of Canada Kingston. Upon commissioning in 1988 he joined the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), and has had the great privilege of spending the majority of his career in command or deputy command positions, including commanding 3 PPCLI, 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group, 3rd Canadian Division and Joint Task Force West, Deputy Commanding General – Operations for XVIII (U.S.) Airborne Corps, Deputy Commander United Nations Command in Korea, Deputy and for a short time Commander of Military Personnel Command, and Commander Canadian Army. He served as the Chief of Defence Staff from February 24, 2021 to July 18, 2024

Operationally, Gen Eyre has commanded a rifle platoon with the United Nations Force in Cyprus; 2 PPCLI’s Reconnaissance Platoon with the UN Protection Force in Croatia (including the Medak Pocket); a rifle company in Bosnia with NATO’s Stabilization Force; the Canadian Operational Mentor and Liaison Team in Kandahar, Afghanistan advising 1-205 Afghan National Army Brigade in combat; as the Commanding General of NATO Training Mission – Afghanistan, where he oversaw the force generation, institutional training, and professional development of the Afghan National Security Forces; and as the first non-U.S. Deputy Commander of United Nations Command Korea in its 69 year history, and as such was the most senior Canadian officer ever permanently stationed in the Asia Pacific region. Among various domestic operations, he was the military liaison to the Government of Manitoba for the 1997 floods, commanded a company fighting the 1998 British Columbia wildfires, commanded the Task Force that secured the 2010 G8 Summit, and commanded the military response to both the 2015 Saskatchewan wildfires and the 2016 Fort McMurray, Alberta evacuation.

As a staff officer, Gen Eyre has served with the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Land Force Western Area Headquarters, in the Directorate of Defence Analysis at NDHQ, and as the J3 of Canadian Expeditionary Force Command. He is a graduate of the U.S. Army Special Forces Qualification Course, the U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College, the U.S. Marine Corps School of Advanced Warfighting, and the U.S. Army War College. He holds a Bachelor of Science and three master’s degrees (Military Studies, Operational Studies and Strategic Studies). His decorations include the Commander of the Order of Military Merit, the Meritorious Service Cross, the Commander-in-Chief Unit Commendation, the Chief of the Defence Staff Commendation, the Order of National Security Merit from South Korea, the National Order of the Star of Romania in the rank of Commander, the French National Order of Merit in the rank of Commander, and was four times awarded the U.S. Legion of Merit, including two in the rank of Commander.

Lieutenant-Colonel (retired) W.G. (Bill) Cummings, CD, is a highly-experienced infantry officer from The Royal Canadian Regiment. His 36 years of uniformed service include operational tours in Cyprus, Bosnia and Afghanistan. Bill is currently employed as a civilian as the Senior Staff Officer Professional Concepts and Development at the Canadian Defence Academy in Kingston, Ontario.

Over the last several years, we have put much emphasis on “character” as central to who we are as members of the Canadian Armed Forces. The concept of “competence,” where we have traditionally focused, remains vital, but not as much as character. Character leads, competence follows—meaning that with good character as a foundation, competence can be built. To take this further, arguably most of our strategic failures over the past half-century have been the result of flaws in character, not competence. Thus, its centrality in our new professional ethos, Trusted to Serve.Footnote 1

So, what is “character”? Many people use the term character, but few take the time to understand its true meaning. The Concise Oxford dictionary cites character as the mental and moral qualities distinctive to an individual.Footnote 2 The Concise Oxford is channeling an over 2,300-year-old understanding of character originally established by Aristotle, who viewed virtueFootnote 3 as both intellectual—meaning the excellence of reasoning powers in terms of prudence and wisdom, and moral—meaning the control of emotions or desires in obedience to reason, in terms of temperance. Character is about pursuing such virtue as a way of being. Aristotle’s conception was based on an understanding that humans find their highest purpose in the active pursuit of a life well lived, a virtuous life.

Recent study of the concept of character by Positive Psychology researchers builds on the work of Aristotle and many others to posit that, from an internal perspective based on trait theory, character is founded upon a set of virtues supported by character strengths.Footnote 4 Academics have taken this research further to develop a leader model based on character whereby character is comprised of values, virtues and personality traits.Footnote 5 Whether a value, virtue, trait, or strength, each represents a positive statement towards human thriving and excellence that echoes Aristotle’s conception of phronesis or practical wisdom.

David Brooks provides an enlightening insight into character when he describes “résumé versus ‘eulogy’ virtues. Résumé virtues ‘are the ones you list on your résumé, the skills you bring to the job market’ and are akin to the competence discussed above. Eulogy virtues are more character oriented, and ‘are the virtues that get talked about at your funeral, the ones that exist at the core of your being—whether you are kind, brave, honest or faithful.’Footnote 6 In the sense of the military profession, to combine the two, a professional life well lived is one that strives for excellence in living the military ethos and pursues the highest levels of professional competence in a virtuous, or positive manner.

One might ask then, what exactly are the virtues? Marcus Aurelius summed it up well when he said, ‘A person’s worth is measured by the worth of what they value.’ What we value as a profession is summed up in our military ethos. Our ethical principles, military valuesFootnote 7 and professional expectations set the standard for how we achieve military results. Ultimately, a professional life well lived is living what the profession values, so that there is no gap between what we think, say, and do.Footnote 8 This is leading a life of integrity; it is not an easy path, and the work is never done. There is no perfection; there are always areas for improvement. Like physical fitness, it requires commitment as a professional daily practice: living the profession’s ethos and pursuing the highest standards of personal character and professional competence—in a word, professionalism. For this reason, the ethos is not something that is read once and then left on the shelf to collect dust. It needs to be our constant companion and guide.

It is in times of adversity—personal and professional—that genuine character manifests.Footnote 9 ‘The true test of character is whether you manage to stand by lived values when the deck is stacked against you. If personality is how you respond on a typical day, character is how you show up on a hard day.’ Footnote 10 It is in these trials that the negative characteristics of ego can manifestFootnote 11, where embracing a sense of victimhood and/or entitlement runs roughshod over asserted values and true character emerges. We are in a profession that prepares for, and occasionally practices the most challenging of human endeavors—war—and thus strength of character is essential. Hard days are what we do.

Since the publication of Trusted to Serve, the CAF has had more time to delve into the concept of character and unpack it. What we have come to realize is that the military ethos alone is insufficient to fully impart the values and virtues that sailors, soldiers, aviators, and operators need to internalize and live if the CAF is to become a better place to work and a more effective military force. Why? Because human behaviour is complex and defies nuanced description by an ethos containing only about twenty terms. Remember, an ethos is only a characteristic spirit of an organization, which in essence describes a profession’s idealized identity. It is not the full description of the organization’s norms and practices, which at times has led to some serious failures in professionalism in terms of character. Certainly, that lived culture has privileged ways of being, especially in terms of narrow leadership approaches focused predominantly on competence and results, which have reduced our military’s effectiveness by harming subordinates, marginalizing others, and diminishing trust across our teams.

Can character be taught? Great minds have wrestled with this question for millennia. While some believe it is innate and fixed, others believe it can be developed. We are in the camp of the latter, but it requires constant effort: "Moral excellence, according to Aristotle, is the result of habit and repetition.Footnote 12" Petersen and Seligman speak of developing character strengths through practice (moral habit).Footnote 13 Crossan, Seijits, and Gandz echo this approach in terms of intentionally developing character dimensions and elements Aristotle’s way, through a commitment to practice.Footnote 14

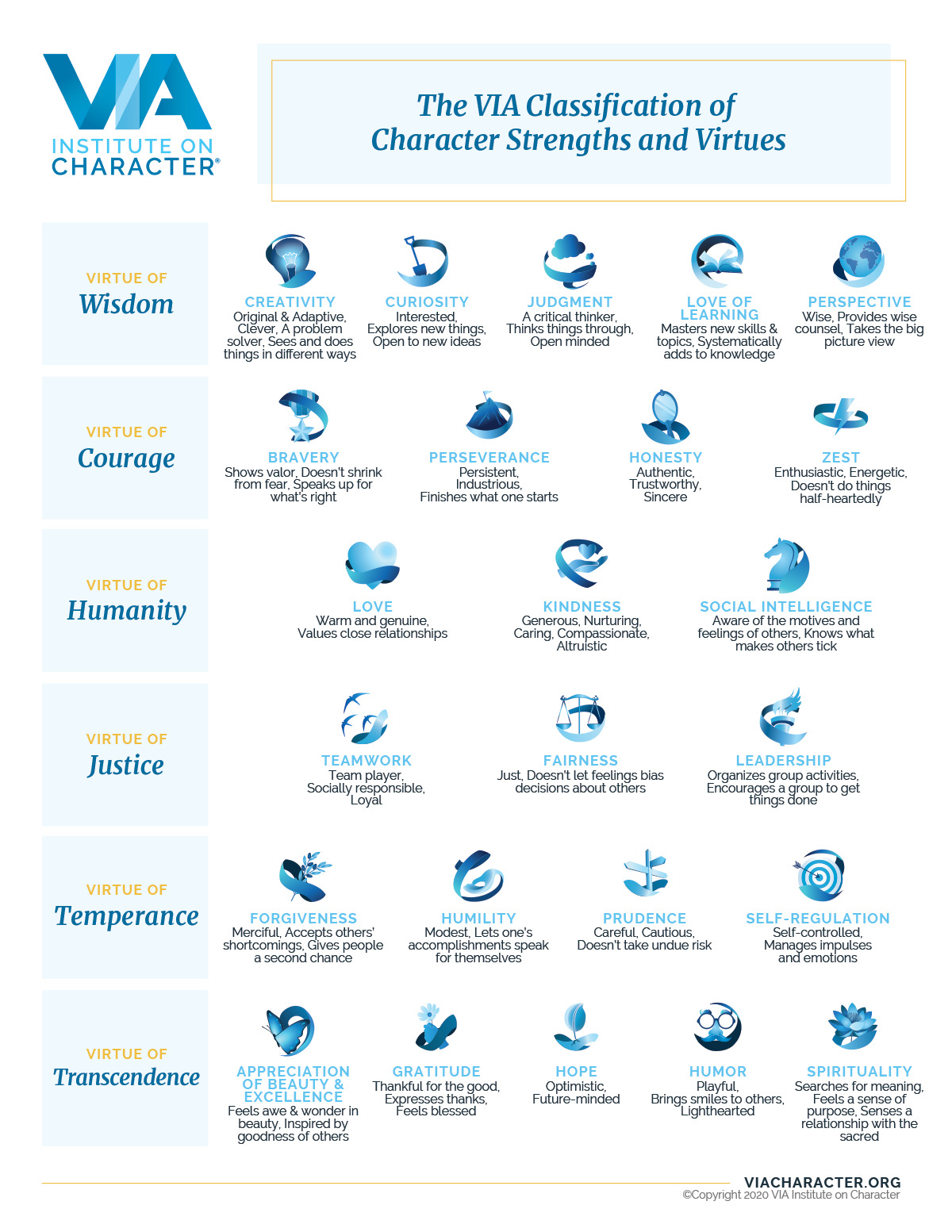

It is for this reason that we are moving towards positive leadership models based upon a set of universal virtues and character strengths which transcend ethnicity, culture, religion, and time, and that reside in everyone. The universal virtues and character strengths stem from the foundational research of positive psychologists Petersen and Seligman into a classification of universal virtues and character strengths for human thriving.Footnote 15 Twenty-four character strengths build to support six core virtues of wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance and transcendence.

Building on this foundational research, The University of Western Ontario Ivey Business School’s Leader Character Framework adapts these virtues and character strengths into eleven interdependent character dimensions and fifty-three supporting elements working together, with the character dimension of judgment fulfilling the special role of mediating “…the way that the other dimensions determine individuals’ behaviours in different situations.”Footnote 16

Both the VIA classification of character strengths and this transformational leadership approach have, enhanced individual and team wellbeing and sustained excellence as their goal. Therefore, it is entirely in harmony with our extant leadership doctrine, ethos, and the imperative of military effectiveness. Key to this Leader Character approach is a focus on improving our leaders” judgment so that the military imperative of mission success and the welfare of our teams receive a more balanced consideration in military decision-making regardless of the nature of that military duty.

It will come as no surprise when we say that leadership, like living the military ethos, is a constant professional practice. For the ethos it is pursuing professionalism, for leadership it is developing strength of character. It is the mindful habit of ensuring that what you think, say, and do aligns with our ethos and the leader character strengths as we perform our military duty. But the question that begs asking here is, “How does one live the ethos and how does one develop strength of character?” And to be fair, we as the profession of arms need to do better in this area than we have done in the past. Our colleges and individual training establishments have done a good job of providing theoretical frameworks and knowledge, but the profession has not placed enough emphasis on experiential learning in the workplace, where this new knowledge needs to be reinforced and mastered.

The process of living the ethos more strictly or developing one’s character strengths is identical and frustratingly simple, yet difficult to implement. The method for living a professional life of character, whereby there is no gap between think, say, and do, is Aristotle’s method—becoming while doing. Internalizing, living, and developing values and virtues is no different than learning how to play guitar or swim competitively. It requires the intention and commitment to develop this competency in terms of time, effort, persistence of habit, and mindset. It helps to develop this competency with a group of like-minded people who have a similar commitment to pursuing excellence in that competency, and who will also provide you frank yet helpful feedback and positive support. This feedback is critical, as aspects of our character are built up or toned down based on use or lack thereof, and honest feedback from those around us is required to see this ebb and flow if we are to be successful in this lifelong commitment.

Research by Tascha Eurich indicates that one of the many challenges that face us in this journey is that only about 15% of people are truly self-aware. Self-awareness has two aspects—internal and external. Internal self-awareness is “ … how clearly we see our own values, passions, aspirations, fit with our environment, reactions …, and impact on others.” In a sense it is what Marcus Aurelius believed in knowing what one values. Though some research indicates that reflection in-action and reflection on-action are ways to achieve self-understanding,Footnote 17 other research indicates that more than just introspection is required.Footnote 18 To be clear, self-reflection and introspection are still required to come to an understanding of oneself, though we need honest feedback from those around us to best understand our biases that come to affect such reflection and introspection.Footnote 19

The second component, external self-awareness is “ … understanding how other people view us, in terms of those same factors listed above.”Footnote 20 Given that the majority of people are not self-aware in general, it should come as no surprise that in order to change in a meaningful direction most people will need relevant and constructive feedback from those people around them. In effect, living the military ethos and developing strength of character to improve one’s leadership potential are both team-based activities.

If our desire is to develop strength of character in leadership, as we should, then the most important group of people around us to solicit feedback from is our subordinates. Although we have a formal performance review process for developing our subordinates, which has implications for career progression and command succession, the CAF does not have a widespread mechanism for upward feedback for purely developmental purposes.Footnote 21 This is where leaders at all levels need to accept the risk, bridge the power-distance gap, and create the leadership climate for such upward feedback for developmental purposes. The risk of which we speak is not risk to the team, but risk to the leader’s ego. Ryan Haliday reminds us, “ … [L] earn from everyone and everything… Too often, convinced of our own intelligence, we stay in the comfort zone that ensures that we never feel stupid (and are never challenged to learn or reconsider what we know). The second we let the ego tell us we have graduated, learning grinds to a halt.”Footnote 22 And such self-assessment needs to be informed through honest feedback from those around us.

Probably the most important aspect to developing strength of character or living the military ethos is one’s mindset. Carol Dweck’s research tells us that a growth mindset is the belief that abilities can be cultivated and that a growth mindset is the starting point for change.Footnote 23 Talent only takes us so far. Those with a growth mindset understand this and use their humility to know that they could be better and their curiosity to seek ways to achieve it. Angela Duckworth’s research reinforces this by showing us that effort counts twice towards success, and that grit, or the passion and perseverance to see something difficult through to completion, is also required to ensure that we put that effort in.Footnote 24 Like fighting spirit, it is the determination to commit to and pursue this learning and change as a daily habit or practice.

Key to developing this positive experiential learning environment are the leaders’ personal examples of courage, humility, and vulnerabilityFootnote 25 in creating that safe psychological spaceFootnote 26 to share each other’s varying perspectives so that we can all better connect and grow in strength of character and move closer to a life of professionalism. Dr. Brené Brown’s foundational research on vulnerability and connection tells us that the two most powerful forms of connection are love and belonging. Belonging is described as the “ … innate human desire to be part of something larger than us,”Footnote 27 which is something that all military professionals can relate to. Brown goes on to further explain that “ … [c] onnection is why we are here. We are hardwired to connect with others, it’s what gives purpose and meaning to our lives.”Footnote 28 Many military professionals believe that sharing one’s professional difficulties with their subordinates would erode their subordinates’ confidence in their superior’s leadership. Actually, it is the other way around. Having the courage to be authentic about one’s challenges with others allows people to better connect with you, and Brown’s deep research demonstrates this time and again. We connect with people’s humanity, not their perfection.

Photo: Corporal Morgan LeBlanc, Canadian Armed Forces photo

Students on the Infantry Officer Development Period 1.2 Course (Infantry Mechanized Platoon Commander Course) receive a set of orders during the assessment phase of the course at the Infantry School Combat Training Center, 5th Canadian Division Support Base (5 CDSB) Gagetown, New Brunswick, November 26, 2021.

Upward feedback is not innovative, but it is essential to develop better leadership. CAF doctrine identifies it as reverse mentorship.Footnote 29 Our challenge is that we have not developed a supportive culture that allows for the safe flow of that much-needed feedback, especially from our subordinates, for purely developmental purposes, even though we have made it clear in Trusted to Serve that is it entirely acceptable for a junior military professional to respectfully correct or provide feedback to a senior military professional. Similarly, our mentoring networks and frameworks that would facilitate such dialogue are not well established and resourced to do so. Not that such exchange of perspectives need be strictly facilitated by a formal mentoring program. Other organizations such as the Canada Revenue Agency have been successful in implementing a digital feedback system for purely character-related developmental purposes.Footnote 30

There are many ways to connect with people and we do not necessarily need more institutional tools to do so. Rather, we must prioritize courage, humanity, vulnerability, and humility to better connect with the people in front of us in more meaningful ways that inspire trust. That trust will allow for a more permissive environment for the candid exchange of perspectives that will help everyone involved grow in strength of character and deepen their levels of professionalism. We are significantly short on personnel right now and everyone is pressed for time in achieving results. However, if we do not take the time to develop our subordinates more equitably and allow their feedback to shape our leadership character, we are missing an opportunity to accelerate experiential learning within the profession of arms that will generate higher levels of military effectiveness. Character can be developed, and becoming better every day is a true sign of military professionalism. Our people and our country deserve no less.